Before reading this case study

Before reading this case study, it is strongly recommended that you read Chapters 1 (introduction, which introduces the SRL approach and discusses how the ethnographic data is used in the case studies), 2 (detailed explanation of the modelling approach), 5 (ethnographic research that informed the case studies), the relevant bits of 6 (background information to the case studies, including excavation history and notes about chronology), and 7 (the SRL template) all of which are essential to an understanding of how the case studies were compiled and what they are designed to achieve. The case studies were never designed to be read as stand-alone pieces. Chapter 9 compares the case studies, and may be of interest to those who are interested in different approaches to livelihood management in dryland areas.

As explained within the thesis, my priority was to test the Sustainable Rural Livelihood model, which was derived from development economics. This means that the emphasis was on pushing the data to the absolute limit. This has resulted in speculative scenarios that match the data, many of which are by no means the only possible explanations and are open to challenge. I believe, however, that some speculation is a healthy move towards the creation of hypotheses that can be tested rather more empirically, and hope that the speculative relationship between the published data and my speculative extrapolations is made explicit.

You can read and print the case study from this page, but you can also download it as a PDF here.

1.0 Introduction

The following section discusses the Late Neolithic of Nabta Playa, the Ru’at el-Baqar, within the framework of the Sustainable Rural Livelihood approach and is divided into the sections described in Chapter 6. An introduction to the case study is provided in Chapter 7. The Ru’at el-Baqar dates 7350 – 6600 cal BP or 5400 – 4650 cal BC. The site with the most complete stratigraphic record of the Nabta Playa archaeology, E-75-8, provides dates of 6550-5800bp (5200-4850 cal BC). The objectives of the case study are to draw out information about options, risk, sustainability and responses to all three in circumstances where a temporary water resource was available only on a seasonal basis. All aspects of the asset matrix contribute to sustainability for communities under conditions of vulnerability, whether overtly relating to economic activities or less transparently by social mechanisms that assist with marginal livelihoods and changes in those livelihoods. The location of Nabta Playa is show in figure 1, together with other relevant sites. A map of the Nabta basin is shown in figure 2.

Figure 1 – Nabta in the context of the Western Desert

Figure 1 – Nabta in the context of the Western Desert

Figure 2 – Map of Nabta Playa.

Figure 2 – Map of Nabta Playa.

Modified from Wendorf and Schild 2001a, fig 1.2, p.5

2.0 The data available for each phase

The main forms of data are summarized in table 1 below, the presence of data indicated by “yes” and absence indicated by “no” Variations in quality of that data will be discussed throughout the text, and a list of the main sites discussed is shown in table 2.

| Category | Data | Yes / No |

| Site type | Settlement | Yes |

| Cemetery (concentration of multiple burials) | No | |

| Ceremonial (monuments and ritual structures) | Yes | |

| Unknown | No | |

| Architecture | Domestic shelters / foundations | One example |

| Hearths / Steinplätze | Yes | |

| Storage | ? | |

| Ceremonial structures | Yes | |

| Type | Stratified | One site |

| Palimpsest / Chronologically undetermined | Yes | |

| Cave / rock shelter | No | |

| Funerary | Burial structures | Yes |

| Human physical remains | Few | |

| Grave goods | No | |

| Diet | Faunal remains | Few |

| Botanical remains | Few | |

| Environment | Faunal remains | Few |

| Botanical remains | Few | |

| Sedimentary and geomorphological data | Yes | |

| Other environmental / climatic indicators | Yes | |

| Tools/ Craft items | Stone tools | Yes |

| Grinding stones | Yes | |

| Pottery | Yes | |

| Ostrich eggshell | Yes | |

| Basketry, cordage etc. | No | |

| Animal products | Few | |

| Other artefact types | No | |

| Personal or symbolic material | Beads / other jewellery | No |

| Portable art | No | |

| Palettes | No | |

| Cultural components on everyday tools / pottery | Yes | |

| Rock art | No | |

| Prestige objects (potentially) | No | |

| Dating | Radiocarbon dates | Yes |

| Relative / stylistic | Yes |

Table 1 – Data types available for the Ru’at el-Baqar Late Neolithic

| Site | Type of site | Key features |

| E-75-8 | Stratified occupation | The largest of the Ru’at el-Baqar sites. Late Neolithic layer 7, 9 and 10 overlying earlier levels. Hearths, pits, hut, lithics, pottery, worked shell and bone, grinding implements |

| E-77-1 | Occupation | Hearths, lithics, pottery |

| E-92-2 | Occupation | Three separate groups of hearths. Associated with wells and ostrich eggshell |

| E-92-7 | Occupation (extensive finds, 400 x 360m) | Late and Final Neolithic overlying Al Jerar Early Neolithic. NE part of Nabta. Surface finds of 100s of large hearths in different states of preservation, 18 of which examined (3 types), lithics, grinding implements, pottery, bone of domesticates (cattle, sheep/goat). |

| E-92-9 | Stone circle | With surface debris and hearths, possibly associated with the circle. |

| E-94-1N (“Northern Tumulus”) | Tumulus | Semi-articulated cattle burial in a pit beneath sandstone slabs forming tumulus with piece of wood overlying fill. Sheep/goat or Dorcas gazelle remains in tumulus fill. |

| E-94-1S | Tumulus | Sandstone slabs forming tumulus. Disarticulated cattle (up to x3) and sheep/goat remains (x1) and sheep (x1). Lithics (x3) |

| E-94-2 | Occupation | Late and Final Neolithic. Hearths (3 groups), lithics, pottery, notched stones, grinding implements, sparse faunal remains on deflated surface |

| E-94-3 | Occupation | Hearths, lithics, potsherds, grinding implements, notched stones |

| E-96-1 | Complex Structure | Earliest in series of sandstone features constructed over pieces of tablerock. This is the only one dating to the Ru’at el-Baqar; the others date to the Final Neolithic |

| E-96-2 | Tumulus | Undetermined function. Only 19 relatively small slabs and no animal or other remains or artefacts |

| E-96-4 | Tumulus | Remains of disarticulated cattle (x4) and a possible canid. Two lithic tools. |

| E-97-4 | Tumulus | Disarticulated cattle (x2) with tethering stones added to sandstone tumulus |

| E-97-5 | Tumulus | Fragmentary tumulus over remains of single young male human, cranium and other bones absent |

| E-97-6 | Tumulus | Sandstone slabs forming tumulus. Disarticulated cow |

| E-97-12 | Tumulus | Southernmost. No faunal remains. Lithics (x2) |

| E-97-16 | Tumulus | Sandstone slabs forming tumulus. Disarticulated cow (x1) |

| E-97-17 | Burials | Three burials without artefacts, all poorly preserved on the same dune as E-92-9, the surrounding surface dominated by Ru’at el-Baqar material. |

| Alignment A | Stone row | Apparently the earliest of a series of stone rows, this one aligned towards Sirius. |

Table 2 – Ru’at el-Baqar Neolithic sites mentioned in the text

(Source: Wendorf, Schild and Associates 2001)

Table 3 provides a list of the dates listed in Wendorf, Schild and Associates (Schild and Wendorf 2001c, p.53-54, Table 3.1) and calibrated using quickcal2007 ver1.5 (Cologne Radiocarbonn Calibration and Paleoclimate Research Package – University of Cologne http://www.calpal-online.de/index.html).

| Area

|

Site/Feature | Uncalibrated c-14 dates bp

|

Calibrated dates BC | Material | Lab. No. |

| Nabta Playa | E-75-8, Bed 2, A-B/18 | 6440±80 | 5408±66 | Charcoal | SMU-487 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-94-3, Hearth 2 | 6550±60 | 5522±45 | Charcoal | CAMS-16590 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-77-1, Hearth 2 | 6530±95 | 5484±89 | Charcoal | DRI-2877 |

| Nabta Playa | E-75-8, Bed 3a, Lowest Hearth | 6500±80 | 5459±74 | Charcoal | SMU-435 |

| Nabta Playa | E-75-8, Hearth, 10-20cm bs | 6430±75 | 5403±63 | Charcoal | SMU-2504 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-77-1, Hearth 4 | 6350±60 | 5340±88 | Charcoal | CAMS-16590 |

| El Ghorab Playa | Gd-926, Hearth near burial | 6330±100 | 5295±124 | Charcoal | Gd-926 |

| Nabta Playa | E-75-8, Hearth? Bed 4, A-B/15 | 6310±90 | 5271±116 | Charcoal | SMU-441 |

| Bir Murr | Tumulus? Hearth B | 6310±70 | 5294±73 | Charcoal | SMU-1120 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-77-1, Hearth 6 | 6290±60 | 5269±58 | Charcoal | CAMS-17292 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-94-3, Hearth 6 | 6280±60 | 5238±77 | Charcoal | CAMS-19294 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-77-1, Hearth 3 | 6260±60 | 5212±87 | Charcoal | CAMS-17395 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-94-3, Hearth 3 | 6250±70 | 5199±97 | Charcoal | DRI-2873 |

| Nabta Playa | E-94-2, Area A, Hearth 5 | 6220±90 | 5172±112 | Charcoal | DRI-2879 |

| El Balaad Playa | E-79-5B, Hearth B | 6180±70 | 5132±90 | Charcoal | SMU-965 |

| Nabta Playa | E-75-8, Feature 1 | 6155±105 | 5096±131 | Charcoal | DRI-3547 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-94-3, Hearth 1 | 6120±95 | 5062±129 | Charcoal | DRI-2880 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-77-1, Hearth 1 | 6120±70 | 5073±107 | Charcoal | DRI-2872 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-94-3, Hearth 8 | 6070±60 | 4997±94 | Charcoal | CAMS-19591 |

| Nabta Playa | E-75-8, Bed 8, top | 6030±195 | 4952±235 | Charcoal | DRI-3552 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-94-3, Hearth 2 | 6020±60 | 4921±74 | Charcoal | CAMS-16592 |

| Nabta Playa | E-94-2, Hearth 9 | 6000±60 | 4898±75 | Charcoal | CAMS-17287 |

| Gebel Nabta Playa | E-94-3, Hearth 7 | 6000±50 | 4897±62 | Charcoal | DRI-2879 |

| Nabta Playa | E-94-2, Hearth 10 | 5980±60 | 4875±73 | Charcoal | DRI-2884 |

| Nabta Playa | E-94-3, Hearth 5 | 5970±90 | 4869±110 | Charcoal | DRI-2876 |

| Nabta Playa | E-94-2, Area A, Hearth 6 | 5970±50 | 4868±63 | Charcoal | DRI-2883 |

| Nabta Playa | E-92-7, Area A, Hearth 8 | 5940±110 | 4837±133 | Charcoal | Gd-10114 |

| Nabta Playa | E-94-2, Area A, Hearth 4 | 5910±50 | 4790±54 | Charcoal | DRI-2881 |

| Nabta Playa | E-94-2, Area C, Hearth 8 | 5860±70 | 4712±89 | Charcoal | DRI-2871 |

| Nabta Playa | E-94-2, Area A, Hearth 1 | 5840±60 | 5698±77 | Charcoal | DRI-2869 |

| Nabta Playa | E-94-2, Area B, Hearth 7 | 5830±60 | 4688±77 | Charcoal | DRI-2882 |

| Nabta Playa | E-75-8, Hearth | 5810±80 | 4666±96 | Charcoal | SMU-473 |

| Nabta Playa | E-97-6, Tumulus, offering | 5500±160 | 4326±185 | Charcoal | DRI-3354 |

| Nabta Playa | E-94-1, Burial Pit | 6470±270 | 5363±272 | Wood | CAMS-17289 |

Table 3 – Ru’at el-Baqar Radiocarbon Dates

(Source: Wendorf, Schild et al 2001, p.53-4)

3.0 The Livelihood Status

3.1 Asset Matrix

3.1.1 Natural Assets

The following table (table 4) summarizes the main types of zone available for exploitation during the Late Neolithic Ru’at el-Baqar, with zones unavailable shown greyed out and crossed through, maing it clear that this was not a resource that could have supported herders on a permanent or semi-permanent basis.

| Zone 1 | Sahel type / savannah conditions | In a largely featureless landscape, light seasonal rains produce a savannah and scrub type ecology similar to the modern day Sahel, with grassland and shrubs suitable for seasonal but not necessarily year-round herding |

| Zone 2 | Highlands, low hills, high escarpments, Plateaus | Seasonal vegetation, attracting certain vegetation and game, sometimes offering different topologies and ecological niches |

| Zone 3 | Riverine | Permanent water source with floodplains, attracting vegetation, game and containing aquatic resources |

| Zone 4 | Lake / Playa / spring | With the potential for aquatic plants but not fish or other aquatic zoological species |

| Zone 5 | Groundwater zone

|

Runs along the edge of water-filled basins and supports seasonal vegetation, attracting game on a temporary or permanent basis |

Topography

At the time of the first excavations there were no topographical maps available for the Nabta area so most topographical information was derived from aerial photographs taken in the 1960s and GPS readings (Schild and Wendorf 2002, p.12).

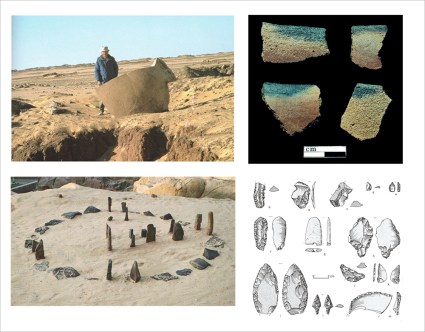

Figure 3 – A view of Nabta Playa

Figure 3 – A view of Nabta Playa

(Source: Schild and Wendorf 2015, p.354 figure 3)

Nabta Playa sits between 22° and 23°N (latitude) and at 32°E (longitude). The central part of the basin measures 14km (east to west) by 10km (north to south) with wadis draining into the basin (Schild and Wendorf 2001b, p.11). A prominent hill called Gebel Nabta sits c.5km to the west of the playa, composed of Nubian sandstone capped with limestone, with a bigger hill of the same composition 32km southwest of Gebel Nabta (Wendorf and Schild 1980, p.82). The surface of Nabta Playa is characterized by sands that stretch in plains interrupted by scarps, low sand dunes, some of them forming strings, and higher fossil phytogenic sand dunes (figure 3) (Schild and Wendorf 2001b; p.11; Wendorf and Schild 1980, p.82). Nubian sandstone forms the bedrock of the Nabta area and appears on the surface in outcrops. Other outcrops of durable basement complex occur to the north and northeast, including pink granite (Wendorf and Schild 1980, p.82). Nubia Formation sandstone and shales form small rises in the east, south and west (Schild and Wendorf 2001b, p.11-2). Approximately 200km to the north, is an Eocene scarp and plateau, c.90m high, formed of sandstones, shales, limestones and marls. The average elevation of the Nabta area is 240m above sea level (Wendorf and Schild 1980, p.83). The landscape is marked by numerous basins and sand-infested wadis (Wendorf and Schild 1980, p.82, 84).

Hydrology

The lakes in the basin at Nabta, known as playa lakes, are “dry lakes” as defined by Leity (2008, p.101), ephemeral rainfall lakes where groundwater is so far beneath the surface that neither water nor the minerals that it holds reach the surface. Following the end of the early Holocene climatic conditions in southern Egypt deteriorated, with a gradual drying of the environment (Nicoll 2004, p.569). The main source of water at Nabta Playa was rainfall that collected in basins and remained in place before evaporation reduced them and dried them out, but these playa lakes were not as extensive as they had been in previous early Holocene humid phases (Schild and Wendorf 2013, p.128). A wadi to the northwest of the basin, now known as the “Valley of the Sacrifices,” was the main low-energy drainage route by which water found its way into the main Nabta basin (Wendorf and Schild 2004, p.11, p.44-45). It is still active today on occasions (Schild and Wendorf 2001b, p.37). Unlike conditions during the climatic optimum in the early Holocene, there is “no evidence of extensive playa lakes” at Nabta during the mid-Holocene during which the Ru’at el-Baqar occupation took place (Schild and Wendorf 2013, p.128), and it is suggested that the volume of water in the basin and sub-basins at that time “was never large and its depth minimal” (Schild and Wendorf 2001b, p.45). Mohamed (2001, p.426) goes into more detail: “There is no evidence that the entire Nabta basin was seasonally flooded at this time . . . . Instead floodwaters from the rains were sufficient only to inundate the smaller basins located at the mouths of peripheral drainages.”

E-75-8 was probably located in the vicinity of a perched water table, which would have enabled wells to be sunk in the depression to access water as it diminished, and water was also held in the deep sandy substratum adjacent to impermeable layers, again meaning that wells could be employed to access water as it retreated (Kobusiewicz 2003, p.97; Schild and Wendorf 2001b, p.47). E-77-1 and E-94-3 were both on the site of a wadi that became blocked by sand dunes and into which water drained and became trapped, potentially forming deep seasonal lakes depending on rainfall (Wendorf and Schild 2001c, p.427). E-77-1 was quite high about the floor of the basin on a sand dune, but sedimentary evidence indicates that the site was covered with water during periods of high rainfall (Wendorf and Schild 2001b, p.454), as well as filling the blocked wadi below.

The smaller playa lakes dried more rapidly than in the early Holocene, and during the mid-Holocene tropical forms of vegetation retreated, to be replaced by Sahelian and desert species, and aeolian deposits were laid down, with only highland and oasis areas continuing to offer long-term predictable refuges for wildlife and people (Barakat 2001; Nicoll 2004, p.569). In the plains of the Western Desert there was little topographical variation to shelter open areas of water from evaporation, which could reach several metres per year in the Western Desert (Kröpelin 2005, p.51). In the immediate vicinity, a number of sub-basins also formed, and a series of other large basins were also used. Of these the most important was Bir Kiseiba, which was only a few days walk away and this too had playa resources that were used during drying periods due to its perched water table (Haynes and Haas 1980, p.715).

Beyond Nabta, in areas that were theoretically within the annual reach of Nabta, the Nubian aquifer, lying over the Basement Complex extends beneath the Western Desert, continued to provide perennial water to Dakhleh and Kharga c.200km to the north, but does not come to the surface at Nabta itself. The highland areas of Gilf Kebir and Gebel Uweinat provided orographic rainfall to the west, whilst the Eastern Desert supplied orographic rainfall across the Nile to the east.

Finally, the Nile was only a few days walk from Nabta Playa, providing another water source for the occupants of Nabta as part of their general patterns of mobility. The same rainfall that filled the basins also watered the desert, which will have restored pastures and annual vegetation, whilst ensuring the survival or arid-adapted perennials including shrubs and trees. The hydrology of Nabta Playa can therefore be characterized as follows:

- Playa resources in the immediate vicinity which were replenished annually by seasonal rainfall, providing highly seasonal and ephemeral resources, particularly where a perched water table was present, both in the main basin and surrounding deflated areas that drained into the main basin;

- Groundwater resources were available via wells as evaporation depleted water levels seasonally;

- Dune-blocked wadis providing seasonal water in temporary lakes;

- In the nearby area other playa resources may have supplemented those at Nabta;

- Other lake systems were available at a distance, dependent on a high degree of mobility;

- Dakhleh and Kharga oases were 200km and several days walk to the north of Nabta;

- The Nile Valley was a two-three day walk away;

- More distant resources were also available if high levels of mobility were supported, including highly ephemeral basins that may have been found in patches throughout the Western Desert (Kuper and Riemer 2013) and highland areas.

It has already been seen how modern pastoralists are highly sensitive to localized conditions (Chapter 5) and how mobility is one of many strategies used to handle it. The hydrology of the Nabta area alone, without other considerations, would have required movement between different areas on a seasonal and perhaps more frequent basis.

Light and temperature

Egypt has high light and temperature quotients throughout the year. The lowest mean annual temperature at Luxor is 13°C in January, the highest 32°C in July and August (Ibrahim and Ibrahim 2003) but a more realistic comparison is probably Dakhleh Oasis. The lowest mean annual temperature Dakhleh is 3.5°C in January, the highest 38.9°C in June (N.O.A.A n.d.). Night time temperatures are lower, but not to the point of being detrimental to livelihood options. Evaporation rates in the Western Desert ere high (Kropelin 2005, p.51) The conditions of high heat and variable shade will have constrained forms of vegetation and fauna that can survive in the desert.

Aeolian conditions

The prevailing winds in Egypt are north-eastern trade winds which, in winter are interrupted by west north-western winds from the Atlantic. In spring and early summer the hot dry dust storms called khmaseen are common (Ibrahim and Ibrahim 2003, p.52), and sweep across the plains of the southern Western Desert, visibly picking up, shifting and redepositing loose surface particles in dense, fast-moving clouds. In the Western Desert aeolian activity has had considerable impact on desert and archaeological surfaces.

Edaphic Conditions

Ibrahim and Ibrahim (2003, p.52-3) describe desert soils in Egypt as aridisols and sandy-rocky desert surfaces. They have low humus content with little biological activity and coarse to medium texture. Matters will have been better in the Holocene, where even sparse perennial vegetation will have helped to secure soil and build up a certain amount of topsoil. All drylands are characterized by low nutrient content of the soil, and particularly an absence of nitrogen, poor water retention and are at risk from soil depletion leading to the risk of poor germination (FAO 2004). The underlying sandy soils that seem to be inferior all ways to floodplain type conditions but they can produce earlier and fast-growing species, which is of benefit to herders (Schareika 2003, p.20). Animal dung will also have contributed to the quality of the soil in rangelands, and particularly where animals sheltered from the sun. Today, the lack of stabilizing root systems combined with an open topography and high winds mean that there is no topsoil remaining.

Vegetation

During the mid-Holocene the Western Desert consisted of dry savanna, with Sahelian type conditions, consisting of “just a little grass after the rains in the summer, and temporary water in closed basins” (Schild and Wendorf 2004, p.11). Groundwater seepage zones will have produced salt-tolerant vegetation for the duration of the lake (Laity 2008, p.99). Table 5 shows the plant species recorded during excavations.

| Plant Species | ||||

| Species

|

Sites | Sample size | Habitat | Reference |

| Acacia ehrenbergiana | E-75-8, E-94-2, E-92-7 | 286 | The most drought and high temperature tolerant of trees in Egypt today. Tolerant of animal browsing. | Barakat 1996, p.64; Barakat 2001, p. 599, Table 22.7; Barakat 2001, p. 597, Table 22.4; Barakat 2001, p. 598, Table 22.5; Springuel 2006, p.68-70 |

| Acacia nilotica | E-75-8 | 33 | Prefers moist conditions, will grow beside pools in oases, tolerant of short droughts and some soil salinity. | Barakat 1996, p.64; Barakat 2001, p. 597, Table 22.4; Springuel 2006, p.74-5 |

| Acacia tortolis raddiana | E-75-8 | 1 | Desert adapted with a preference for non-saline wadis, oases and depressions. | Barakat 1996, p.64; Barakat 2001, p. 597, Table 22.4; Springuel 2006, p.81-82 |

| Capparis decidua | E-94-2, E-92-7 | 1036 | Drought resistant with preferences for silt alluvium. | Barakat 1996, p.64; Barakat 2001, p. 599, Table 22.7; Barakat 2001, p. 598, Table 22.5 |

| Chenopodiceae | E-94-2 | 1 | Drought and highly saline tolerant. | Barakat 1996, p.64; Barakat 2001, p. 599, Table 22.7; Barakat 2001, p. 598, Table 22.5 |

| Maerua crassifolia | E-92-7 | 3 | Tolerant of high temperatures, drought and salinity. | Barakat 2001, p.598, Table 22.5; Springuel 2006, p.94-5 |

| Panicum turgidum | Ceramic impression | Remarkably drought tolerant, and highly tolerant of grazing. | Magid 2001, p.608; Heneidy and Halmy 2009 | |

| Salvadora persica | E-94-2 | 37 | Drought tolerant but not saline tolerant. Thorny scrub or grassland along river banks or on seasonal floodplains. | Barakat 2001, p.596; Barakat 2001, p. 599, Table 22.7; Springuel 2006, p.100-101 |

| Setaria | Ceramic impression | Unspecified | Magid 2001, p.608 | |

| Tamarix sp. | E-94-2, E-92-7 | 1110 | Tolerant of sandy and saline conditions. | Barakat 1996, p.64; Barakat 2001, p.599, Table 22.7; Barakat 2001, p.597, Table 22.4 |

| Ziziphus spina-cristi | E-92-7 | 71 | Not saline tolerant. Prefers alluvial deposits. | Barakat 2001, p.596; Barakat 2001, p. 598, Table 22.5; Springuel 2006, p.107-108 |

Table 5 – Plant taxa present in the Ru’at el-Baqar Late Neolithic

Due to the levels of deflation an exact profile of the vegetation present is not possible but there are clues. The species shown in Table 5 are typical of arid and semi-arid environments. Their root systems form phytogenic hillocks and they pioneer areas around water beds, wells, depressions, wadis and water tables up to 8m deep. They are saline tolerant (Barakat 2001, p.596). In the Ru’at el-Baqar contexts of E-75-8 Acacia ehrenbergiana (30 samples) Acacia nilotica (33 samples), Acacia tortolis raddiana (1 sample) and unspecified acacia species (106 samples) indicate that acacia was well represented. Acacia is very resilient in arid environments where it shares an environment with pastoralists, in spite of frequently intensive grazing, and seeds are propagated by browsing herbivores, meaning that it has a high recovery rate (Selemani et al 2013, p.146). There are also 72 samples of Tamarisk (Barakat 2001). These taxa indicate the availability of a certain amount of low level trees and shrubs whilst three taxa of sedges from E-75-8, suggest marshy environments along playa edges. Tamarisk pioneers around open water bodies, wells, depressions and wadis, but is saline tolerant (Barakat 1996, p.64; Barakat 2001; Wasylikowa et al 2001). At E-92-7 all the hearths combined produced samples of Tamarix, Capparis decidua, Acacia ehrenbergiana, Ziziphus spina cristi, Cassia sp., and Maerua crassifolia (Barakat 2001, p.597). At E-94-2 charcoals from all hearths produced Tamarix sp., Acacia ehrenbergiana, Capparis decidua, Salvadora persica and chenopodiaceae, many of which indicate vegetation in depressions and along wadis, with a tendency towards contracting desert vegetation (Barakat 2001, p.598). Schild and Wendorf describe this as “contracted groundwater-bound desert vegetation accompanied by erratic and poor rainfall” (2001b, p.49). Barakat (2001) discusses a reduction of water-preferring taxa and the appearance of chenopods at E-92-7 and E-94-2, suggesting that they indicate the retreat of Sahelian elements in favour of desert conditions.

The presence of cattle, sheep and goat species are indicative that the local environment and more distant playa basins and more distant areas could be used together to support herds sustainably for the duration of the wet season and its immediate aftermath. Pastoralists need an extensive rangeland to provide the grazing necessary for herds (Wendorf and Schild 1998, p.109), and they would not have returned to Nabta if it could not have provided the necessary fodder and water requirements for herds.

Fauna

All animal remains were of potential use for food as well as the fabrication of tools, leather, textiles, ropes, glue and ornamental items (Hurcombe 2014). An important by-product of animals is dung, which may be used as fuel (Hassan 1988). The species present are shown in tables 6 and 7 below in sample size order, and are the combined data from E-96-1, E-94-1, E-79-5 and E-75-8, as presented by Gautier 2001, table 23.1, p.610-611, p.612-629. It shows the type of environment to which the represented species were adapted, each contributing to a picture of arid and semi-arid conditions.

| Faunal Species | ||

| Data | Sample | Habitat |

| Gazella dorcas (Dorcas gazelle) | 198 | Dry-savannah but not hyper-arid adapted. Can manage without water for long periods, depending on plant moisture |

| Zootecus insularis | 186 | Arid and semi-arid adapted gastropod |

| Lepus capensis (hare) | 176 | Desert adapted |

| Gazella dama (Dama gazelle) | 45 | Desert adapted – can manage without water entirely, depending on food moisture |

| Arvicanthis niloticus (Field rat) | 42 | Human commensal |

| Small birds | 29 | Quails and migratory |

| Reptiles | 22 | Arid adapted |

| Canis lupus (dog) | 14 | Human commensal / domesticated |

| Vulpes vulpes (Jackal) | 13 | Savannah adapted |

| Struthio camelus (Ostrich) | 8 | Arid adapted, chicks need water but adults can survive for long periods on plant moisture |

| Hystrix cristata (Porcupine) | 7 | Preference for savannah to semi-desert |

| Paraechinus aethiopicus (Desert hedgehog) | 3 | The most desert adapted of the hedgehog species |

| Ammotragus lervia (Barbary sheep) | 2 | A preference for lower mountain and stony slopes |

| Small carnivores | 1 | Fenec fox is found in the Western Desert today |

Table 6 – Animal species present in the Ru’at el-Baqar (MNI)

Freshwater gastropods are represented, but all are considered to be imports and are thought not to reflect local conditions at Nabta but are included here for the sake of completeness:

| Evidence for aquatic species in Nabta Playa | |||

| Data | No. | Context ID | Reference |

| Freshwater bivalves | 4 | E-75-8, S-trench (sub)surface | Gautier 2001, p.620, Table 23.1 |

| 1 | E-75-8, spits 1-4 | Gautier 2001, p.620, Table 23.1 | |

| Small freshwater gastropods | 15 | E-75-8, C to F, surface | Gautier 2001, p.620, Table 23.1 |

| 1 | E-75-8, spits 1-4 | Gautier 2001, p.620, Table 23.1 | |

Table 7 – Aquatic species present in the Ru’at el Baqar

Stone, minerals and ores

Although the Western Desert seems fairly barren of stone at first glance, Nabta lies on Nubian Formation Sandstone, which is plentiful in outcrops in the area. Additional sandstone and shale outcrops are found to the east, south and west (Schild and Wendorf 2001, p.11). Intrusions of igneous rocks from the basement complex can be found in the vicinity, notably granite (Schild and Wendorf 2001, p.11; Zedeño 2002, p.54). Although there is no geological database for Egypt to assist with provenancing material types (Aston et al 2000) observations on the ground indicate to the excavators that most of the stones used at Nabta were available locally, including chert, but that the nearest source of flint for stone tool manufacture was a limestone escarpment 70km to the north (Krölik and Fiedorczuk 2001, p.340; Mohamed 2001, p.422) or, further afield, from Kharga and Dakhleh some 200km to the northwest. Both jasper and agate were probably obtained from the Nile, although the authors do not specify where on the Nile (Krölik and Fiedorczuk 2001), so it is possible that it could also have come from the Eastern Desert, where both were also present (Aston et al 2000).

Seasonality

Seasonality is usually considerable for all wild plant and animal species in dryland environments and its character is strongly influenced by rare but valuable rainfall events in the wadis and deserts and may be highly variable and unpredictable both temporally and geographically. At Nabta the dominant species found on occupation sites are gazelle and hare, with some ostrich, all of which could sustain life in the area on a year-round basis, meaning that they offer few insights into of seasonality; hare is highly adaptable to various conditions, ostrich can survive without water for many days except when young; Dorcas gazelle is a mixed feeder with minimal water requirements and Dama gazelle is a mixed feeder with no water requirements (FAO 1999 p.97-8; Pöllath 2007, p.91-2). Ostrich chicks, unlike adults, need regular access to water and it is probable that ostriches were using Nabta as a watering hole and were therefore more vulnerable to capture.

Seasonality therefore has to be assessed by reference to rainfall and the potential movements of humans with their herds. The extremes between wet and dry seasons mean that some areas were only available during the wet season (figure 4). At Nabta the sites were seasonal encampments. Each of them had a specific wet-season attraction, whether it was next to the main basin, on a deflated nearby basin or at the side of a blocked dune lake. There was no possibility of long-term occupation, and there is nothing to indicate that any occupation was of long duration. However, stone-covered hearths and the presence of site furniture (grinding equipment and tethering stones) argue for an intention to return and re-use the site as part of a routine of seasonal activity that included Nabta for short wet-season periods.

Figure 4 – The same pond near Thierola village, Mali, in the Sahel,

Figure 4 – The same pond near Thierola village, Mali, in the Sahel,

during the wet and dry seasons. (Source: Drs. Adama Dao,

Alpha S. Yaro and Tovi Lehmann, National Geographic.

Source: https://bit.ly/2xi8Kvw)

3.1.2 Physical Assets

Settlement location, character and size

Nabta is a perfect example of a “persistent place,” a concept incorporates the idea that certain localities were used repeatedly over the long term, due to their particular characteristics, natural features that attract repeated occupation and the accumulation of material remains at those localities (Schlanger 1992, p.91). In the case of Nabta, the particular characteristics are the playa basin activated by rainfall, the suitability was the resource potential of pasture and game, and the repeated occupation dates from the beginning of the early Holocene. Hofman emphasises that repeated use of the same areas and sites reinforces knowledge about those areas and improves the chances of survival, so scheduled return visits are both practical and desirable (Hofman 1994), whilst Hunn and B. Smith both describe how this type of knowledge becomes embedded in traditions based on a background of memory and past experience (Hunn 1993, p.13; B. Smith 2011, p.263). Smith goes on to suggest that where such areas are perceived to offer predictability and abundance of high value resources, access will be tightly controlled (B. Smith 2011, p.263-4), with complex land tenure agreements in operation, which is supported by other research into land tenure and water rights (Binns 1992; McCann 1998; Dalal-Clayton et al 2003; Dasgupta and Heal 1979; Dika Godana 2016; Holland 1990; Quan 1998). Substantial ceremonial constructions indicate that as well as encampments there were other less tangible assets that may have contributed to the value of the Nabta area.

Unlike the early and middle Neolithic at Nabta, during which settlement structures were constructed, the Ru’at el-Baqar Late Neolithic has a far more ephemeral settlement arrangement. The most prominent and durable remnants of settlement in this period are deflated hearths, where only the lower portions were well preserved (Krölik and Fiedorczuk 2001; Schild and Wendorf 2001b, p.38). The hearths were apparently unenclosed and were used for only brief periods (Wendorf and Schild 2001c), but some of them were very substantial with carefully shaped profiles, and were often stone-lined. The hearths were accompanied by other deflated occupation remains, including surface scatters of lithics, ceramics, grinding equipment, occasional bone and occasional tethering stones (Krölik and Fiedorczuk 2001; Schild and Wendorf 2001b, p.37). Five examples are given below to represent the Ru’at el-Baqar Late Neolithic at Nabta: E-92-7, E75-8, E-94-2, E-77-1 and E-94-3.

E-92-7 (figure 5) is an area of c.400x360m at the northeastern part of Nabta Playa, with Ru’at el-Baqar remains overlying features from the Al Jerar Early Neolithic. The hearths were in various different states of preservation but consisted of often substantial sub-circular constructions of stone slabs between 0.6-1.2m in diameter, none of them very deep. A total of 18 were examined of the 100s found in four areas at the site, some with almost straight sides, floors covered with small slabs and rich in charcoal flakes, and were divided by the excavators into three types of broadly similar features (Krölik and Fiedorczuk 2001).

Figure 5 – Site E-92-7. Area A Hearths 9 and 10.

Figure 5 – Site E-92-7. Area A Hearths 9 and 10.

(Source: Krölik and Fiedorczuk 2001 p.343, fig 9.10)

The hearths were associated with 1060 pieces of debitage, 57 cores, 72 retouched tools on quartz, quartzitic sandstone and flint (materials that made up 83.8% of the total debitage), as well as agate, chert and chalcedony. 60 cores consist of mainly single platform cores, which make up 48% of the core assemblage, most of which are made on quartz. They are followed in frequency by multiple (14%) and ninety-degree platform cores (12%), with opposed platform cores making up only 7.4%. 61% of all cores were made on quartz, 15% on flint, 13% on quartzitic sandstone, and 3.3% on agate. Of the 72 retouched tools, pieces with continuous retouch, notches and denticulates dominated, making up nearly half with only very small numbers of other tools (Krölik and Fiedorczuk 2001, p.338, 346). Grinding implements consisted of 7 fire-cracked fragments of sandstone quarzitic sandstone, sandstone and granite (Krölik and Fiedorczuk 2001, p.349). The pottery sherds found were well made, burnished and smudged. Only two ostrich eggshell beads were found. No botanical remains were recovered. The hearths and the surface scatter were interpreted by the excavators as seasonal camps that remained for short periods each year occupied by cattle and sheep/goat herders who were attracted by the temporary seasonal pools, with each hearth representing a single occupation event (Krölik and Fiedorczuk 2001, p.351).

E-75-8 is a deeply stratified site containing a sequence of earlier deposits, and extends over an area of 500x300m, of which the in situ deposits cover an area of about 75×200/250m (Close 2001, p.352). The site was partially excavated in the mid-1970s and in the 1998 and 1999 seasons (Close 2001, p.352; Nelson 2001, p.386), with the latter excavation units connecting with the earlier ones. A large number of hearths were found, of which ten were excavated, together with a probable hut associated with two pits and a lithic cache. The hearths were basin-shaped and shallow (Nelson 2001 387-389). The largest was 147x120x7cm but most were smaller, not exceeding 70cm in length. They usually contained fire-cracked sandstone rocks, and some contained one or more artefacts, although others did not. The lithic cache contained five bifacially retouched pieces on Cretaceous chert. A possible hut, Hut 1, was semi-subterranean, oval, measuring 275x260x30cm, and contained a number of retouched tools, cores, a hammerstone and handstone and there were five nearby postholes. It contained a clay- and rock-lined basin-shaped hearth with clay lining and several pieces of bone but no charcoal. Two basin-shaped pits were apparently associated with Hut 1 but nothing found within them gave any indication of function (Nelson 2001, p.387-391). Lithic assemblages found in excavations by Close (2001) and Nelson (2001) produced a recognizably Ru’at El-Baqar assemblage, with flint making up 50.3% of the raw materials in the debitage, quartz making up 32.6% and chert 8.6%. These frequencies are fairly consistent with the retouched tool materials with flint at 68%, and quartz at 21.8%.

E-94-2 is also on the northeast side of the Nabta basin, bounded by the remains of a phytogenic dune on the edge of a sub-basin where rain and flash floods deposited playa sediments and where grass and perennials would have germinated (Mohamed 2001, p.412). Excavations were carried out in the hope of finding data about environmental setting and diet within hearth deposits but failed to produce useful data (Mohamed 2001, p.413). Eight radiocarbon dates indicate that it was occupied over a 900 year period, with multiple visits over that period, most concentrated within a 100 year period at around 5900bp (4787 cal BC). The site consists of three separate dense concentrations of hearths, some rather deflated, others well preserved, each consisting of between 18-23 hearths, the groups separated by 100-120m (Mohamed 2001, p.412). There were also additional hearths away from the main groupings. Most were elongated ovals, between 12 and 23cm deep, most with straight walls and some were deeper at one end than another, sloping upwards to the south or southeast. Hearths contained various small sandstone slabs, either as lining or along the bottom, probably used as a barrier between the fire and the soil, and to improve ventilation (Mohamed 2001, p.416). Some contained a small number of artefacts. They were covered with stones and rocks when finished with, apparently to protect them for when they were needed another time. Three wells are associated with the site, 2-3m in diameter and 2m or more deep. Surface finds included 853 pieces of debitage, 31 cores and 39 retouched tools. The usual range of raw materials was used, with quartz, flint and quartzitic sandstone dominating, except in the debitage where Egyptian flint and quartzitic sandstone are followed in volume by chert. Agate, petrified wood, chalcedony, basalt and granite were also employed (Mohamed 2001, p.417, Table 12.1; p.418, Table 12.6; p.419, Table 12.11). Again, single platform cores dominate, followed by initially struck and patterned multiple cores, none of which were subjected to much preparation, if any. Retouched tools are dominated by denticulated flakes, pieces with continuous retouch and notched flakes, and are crafted mainly on flint, rarely on quartz, and some were made on reused Levallois flakes (Mohamed 2001, p.422). Others in very low numbers are notched or denticulated blades, geometric microliths, and a small number of other types found in single numbers. Particularly skilled bifacial pieces included by Mohamed (2001, p.424, Figure 12.8) are an ounan point, a bifacial barbed and tanged arrowhead, bifacial foliate points and other examples, but as these are exclusively surface items it is entirely possible that they belong to the Bunat el-Ansam Final Neolithic. There is no separate area in which manufacturing activities have been identified, and it seems as though suitable materials were brought to the site to be worked, although not in the vicinity of the hearths themselves, which were apparently used as living spaces (Mohamed 2001, p.422). There were no house-like structures associated at the site, no storage pits, and there was no observable significance to the clustering (Mohamed 2001, p.426). Taking all the data together with the low volume of artefacts, occupations were probably brief, with two or three hearths at a time representing single occupation events (Mohamed 2001, p.426).

E-77-1 is located on a phytogenic dune on the western edge of Nabta Playa where a large deflational basin drains into the main basin via a wadi that was blocked by the formation of a dune around existing vegetation. The blockage of the wadi formed a lake following rainfall (Wendorf and Schild 2001b, p.427). The site’s location would have sheltered the site from northerly winds. It was excavated in 1977, 1990 and 1994. It consists mainly of stone-filled hearths surrounded by grinding stones, flaked stone, pottery sherds, and fragments of bone. Although it lies over Al Jerar Early Neolithic deposits, all the hearths were dated to the Ru’at el-Baqar. They are very much as described above at other sites, with circular and oval outlines, lined with fire-cracked sandstone slabs and filled with ash, charcoal and burned sand. Debitage includes flakes and blades, flakes from single platform cores and flakes from multiple platform cores and are “almost casual in character” (Wendorf and Schild 2001, p.438). Cores appear to have been made on quartz, but the cores of Early and Late Neolithic are treated together as a single unit (Wendorf and Schild 2001b, p.438-439). Radiocarbon dates indicate a long period of repeat use (Wendorf and Schild 2001b, p.433).

E-94-3 (figure 6) is at the eastern edge of the lowest part of the sub-basin near which E-77-1 is located on the west of Nabta Playa, and sits on deflated playa sediments (Wendorf and Schild 2001b, p.427). It consists of deflated scatters of cultural debris over an area of c.150x50m, comprised of fire-cracked rocks, lithics, pottery sherds and hearths, of which ten intact examples were excavated. The surface scatter was not collected systematically, but a “grab sample” was picked up including some lithics and potsherds, including some very fine bifacially flaked leaf-shaped and stemmed projectile points including at Ounan point, but it is possible that these belong to the subsequent Bunat el-Ansam. Two shallow trenches were excavated near the surface of the scatter. The site was flooded seasonally during summer rains (Wendorf and Schild 2001b, p.457). Grinders and handstones littered the site, most broken. The hearths are in at least four clusters with possibly two more. Each was a shallow oval basin with a maximum length of 65cm, width of 38cm and depth of 25cm. They are floored with sandstone slabs and have burned silt walls that slope inwards. The fill consists of charcoal and sand.

Figure 6 – Site E-94-3, showing a small stone-filled

Figure 6 – Site E-94-3, showing a small stone-filled

hearth before excavation (Source: Mohamed 2001, p.456, figure 13.14

Although E-92-9 is usually discussed in terms of the stone circle in that part of Nabta, it is worth noting that it is surrounded by rock-lined hearths and surface scatters with lithics, pottery, groundstone remains of the same sort that have been described above (Applegate and Zedeño 2001, p.463-464) and fragmentary, unidentifiable faunal remains (Applegate and Zedeño 2001, p.464). It was located at the end of a wadi on a young fossil sand dune at the northwest of the site, extending over around 2 hectares. A typical dominance of notches and denticulates was found. Low quantities of well-made pottery were almost certainly brought to Nabta, as there are no signs of local manufacture. Three undated burials were found close to the circle on the same dune mound, one topped with a few small Nubia sandstone slabs, collectively called E-97-17 (Applegate and Zedeño 2001, p.464).

In summary, the Ru’at el-Baqar sites are usually clusters of hearths unaccompanied by other structural components, and are surrounded by occupation debris, including tools and the by-products of tool production, grinding equipment and some animal bone. An exception is Hut 1 at E-75-8, but this is an isolated example from which it is inadvisable to extrapolate. Occupation appears to have been brief, but hearths and grinding stones formed site furniture indicative of the intention to return to the site and appear to form part of an infrastructure of mobility pursued by the visitors to Nabta in the Ru’at el-Baqar.

Shelter

Nelson (2001, p.389-391) describes a hut, Hut 1, at E-75-8, which was semi-subterranean and accompanied by a stone-lined hearth and two pits. It is the only known example dating to the Ru’at el-Baqar.

Raw material acquisition

The following graph (figure 7) shows debitage raw material frequencies at three excavations reported in Wendorf, Schild and Associates (2001 Table 9.9, p.346; Table 10.5, p.364; Table 11.5, p.402), indicating a dominance of quartz, followed by flint and chert, although the figures do not always correspond to frequencies for tool types. Unfortunately raw material frequencies were not shown for all sites, but this does usefully show how quartz was becoming more important, than flint that dominated in the Ru’at el-Ghanam Middle Neolithic. Close says that her excavations at E-75-8 produced double the quantities of quartz in the debitage from the Middle to Late Neolithic, tripling amongst cores and increasing by a factor of 10 in retouched Close 2001, p.374). Apart from the excavations by Nelson (2001), referred to in the graph as E-75-8(2) to distinguish it from the excavations by Close (2001) referred to as E-75-8(1), quartz is at least as important as flint and often more so.

Figure 7 – Raw materials from numbers of items of debitage at

Figure 7 – Raw materials from numbers of items of debitage at

three sites at Nabta Playa in the Ru’at el-Baqar (totals compiled from Wendorf,

Schild and Associates 2001, Tables 9.9, p.346; 10.5, p.364; 11.5, p.402).

As mentioned above, most stone types used were available locally, including chert. Agate and jasper were not available locally and although Krölik and Fiedorczuk (2001) mention that it may have been sourced from the Nile, it is equally possible that it came from the Eastern Desert, where it is certainly found (Aston et al 2000). Specialized knowledge would have been required to identify and locate the material. It seems likely that with the possible exception of agate and jasper, no particular difficulty was associated with the acquisition of the appropriate materials for tool manufacture. Chalcedony, chert, petrified wood, quartz and quartzitic sandstone, the main materials used, were available within a 10km distance (Wendorf and Schild 2001c, p.435). Chalcedony, which as in the Ru’at el-Ghanam Middle Neolithic was used to make microliths, was probably available locally in the form of small pebbles in playa silts and wash (Nelson 2001, p.395). The only question-mark lies with flint, which would be easily identifiable but was only available at a distance of 70km to the north (Mohamed 2001, p.422; Krölik and Fiedorczuk 2001, p.340), where it was found in Eocene limestone, a 140km round trip, could either have been acquired by resource acquisition parties or by trade/exchange. At E-75-8 quartz is much more important in the assemblage than it had been in the Ru’at el-Ghanam Middle Neolithic, doubling in volume in the debitage and almost trebling in the cores. Of the fine materials, flint was preferred, but other fine-grained types were also represented, including chert and chalcedony, meaning that fine-grained materials remained the same, suggesting that non-flint fine-grained materials may have been more easily acquired alternatives to flint (Close 2001, p.375).

Ground stone tools were made of sandstone, granite and basalt, which were available in the area (Wendorf and Schild 2001c), although no quarry has been identified in the publications.

The tumuli and the stone circle were made of the local Nubian Formation sandstone blocks, which was in plentiful supply. The local sandstone may have been chosen to ensure the durability of the structures themselves, but it may also have been selected because more pliable materials, like wood, were in short supply. It is also possible that it was chosen because it was representative of the Nabta landscape and all the ideas associated with it. At the moment it is not possible to state whether the use of sandstone was a positive choice or the default option.

Raw materials employed in tool and object manufacture demonstrate both a process of selection and a strategy for acquisition, which differed from that of the Ru’at el-Ghanam Middle Neolithic due to the lack of flint in assemblages, with a preference for locally acquired materials.

Quarries for the raw materials have not been identified, so it is not known what sort of tools or methods were used to extract stone from outcrops.

A different type of resource is pasture. Unlike stone or clays, pastures and marshes that form during periods of rainfall are highly seasonal and move around both geographically and temporally depending on where that rainfall is deposited. As described in Chapters 3 and 5 the hallmark of arid and semi-arid areas is variability, and those using Nabta will have had mechanisms for assessing the value of Nabta season to season and of responding to that information.

Food acquisition and production technologies

Lithic tool technologies

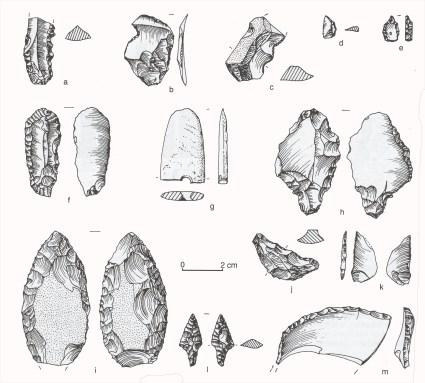

The main fabric to survive in the form of implements is stone. As above, most tools were made partly on locally available materials but flint was also important, which was not available locally, and there are some stone types from outlying areas as well, particularly agate and jasper. At E-92-7, 1060 pieces of debitage, were found, as well as 57 cores and 72 retouched tools made on quartz, quartzitic sandstone and flint (materials that made up 83.8% of the total debitage), as well as agate, chert and chalcedony. Examples of Ru’at el-Baqar tools are given in figures 8, 9 and 11. Of the cores, most were single platform cores, but multiple platform, opposed platform are also found, most of very similar size and made mainly on quartz and flint. Of the retouched tools, dominant forms are notched flakes, denticulated blades and denticulated flakes, making up nearly half of the tools, but some microliths in range of forms are also present, including 20 pieces with continuous retouch. Debitage at E-75-8 consisted primarily of flakes with blades in a minority. Single platform cores again dominate at 58% of the total cores, with Ninety-degree platforms next (17.2%) and the other types making up less than 10% between them (Close 2001).

Figure 8 – A selection of Ru’at el Baqar lithics from E-75-8 (Nelson 2001, p.396).

a, c denticulates; b, notch; d, lunate; e, varia; f, endscraper; g, groundstone;

h, retouched Aterian point; i, biface; j, crescent/lunate; k, backed piece;

l, bifacial projectile point; m, retouched side-blow flake

Different techniques were used for reducing fine-grained and quartz cores and for the use of primary, secondary and tertiary flakes (Close 2001, p.376), with quartz largely left without retouch, indicating that different materials had different roles and were perceived differently. There was very low usage of coarser materials and these too were treated differently from quartz and fine-grained materials (Close 2001, p.376). Materials were clearly carefully selected for different roles in the subsistence strategy.

Of the retouched tools, notches, denticulates and pieces with continuous retouch dominate, and overall there is an absence of geometric microliths made mainly on flakes. Bifaces also appear for the first time in the retouched tool repertoire, with a large number on side-blow flakes. Tools include a large number of pieces with continuous retouch, followed by notched flakes and denticulate flakes and a much smaller number of denticulate blades, truncations, projectile points and microliths, made on a variety of materials (Nelson 2001, p.401-403), a strategy that shows no particular preference for matching a specific raw material to a specific tool type for larger tools. There are examples of only a few other tool types, there are no burins and only very few microliths, although they are still present, and most were made on fine-grained and easily worked chalcedony (Nelson 2001, p.395). One roughed-out celt was found.

Figure 9 – Site E-94-3 Retourched Tools. a, Endscraper on reused Levallois flake;

Figure 9 – Site E-94-3 Retourched Tools. a, Endscraper on reused Levallois flake;

b and f, perforators; c and d, points; e and h, denticulates; g, i and j pieces

with continuous retouch (Source: Mohamed 2001, p.459, figure 13.15)

Close states that between the Middle and the Ru’at el-Baqar Late Neolithic, apart from raw material choices “there is a profound underlying continuity in the predominance of pieces with continuous retouch, denticulates and notches” (2001, p.377). However, Nelson draws attention to differences between the lithic strategies of the two periods, including core reduction, which changed from a microblade to a flake/sideblow flake strategy, the beginnings of invasive thinning and bifacial flaking, the appearance of large numbers of sideblow flakes, a thicker length to width ratio, and the introduction of longer and heavily retouched projectile points (Nelson 2001, p.410), whilst Wendorf and Schild (2001c, p.655) point to the introduction of ground and flaked celts that have lenticular cross sections and polished cutting edges.

Wendorf and Schild (2001c, p.438) suggest that the shift from flint and chert in the Ru’at el-Ghanam Middle Neolithic to quartz in the Ru’at el-Baqar may be due to technological changes accompanying the shift from blades to flakes. It is interesting to note that at E-75-8 whilst quartz is much more important in the assemblage than it had been in the Ru’at el-Ghanam Middle Neolithic, flint was the preferred fine-grained type, but other fine-grained types were also represented meaning that whilst materials changed, the need for fine-grained materials remained the same. This suggests that non-flint fine-grained materials may have been more easily acquired alternatives to flint. Assuming, therefore, that cultural and industrial preferences for fine-grained material continued, Close argues that it was probably the cultural landscape itself that changed, including the access to sources of flint, thereby raising the cost of procurement and leading to other fine-grained rocks to be selected when necessary (Close 2001, p.375). This idea is supported by Nelson (2001, p.401) who draws attention to the more varied raw materials in the Ru’at el-Baqar, including chert, jasper and agate, which may have replaced flint.

The manufacturing industry described above is one of minimal investment of time and energy, representing a low risk strategy. Tools were versatile rather than specialized, although the tasks for which they were required may have been highly specific, requiring large numbers of denticulates and notches, and some bifaces as well as a selection of other tools in smaller numbers. The dominance of single platform cores, making up 58% of the assemblage (Close 2001) also argues for an opportunistic approach to tool manufacture, with low instances of either core or tool curation. A small proportion of the assemblage required higher levels of planning, skill and time and these were evidently required for either specialized tasks or to demonstrate a particular affiliation with certain tasks or ideas, or a combination of task-related production and cultural outputs. All of the flaked tool items were portable. Raw material acquisition patterns changed, with flint no longer represented in high volumes, but replaced with equivalents that were usually available within reach of the Nile. This seems to reflect not a change in preferred raw material but in its accessibility as well as availability. The provisioning strategy in terms of lithics alone was one of provisioning people, but to this should be added that grinding stones and hearths suggest also a provisioning of place. The chaîne opératoire was not a sophisticated one and there are no indications of any particular cognitive input, design or planning.

Figure 10 – Criteria for assessing tool manufacturing strategy

Figure 10 – Criteria for assessing tool manufacturing strategy

(based on Shea 2013, p.39-45)

Using Shea’s observations about costs and benefits as a guideline (figure 10) (2013, p.39-45) the lithics can be assessed in terms of the decisions that were made during the Ru’at el-Baqar. Wendorf and Schild describe the industry of the Ru’at el-Baqar Late Neolithic as “a less skilled and less formal, almost casual, character” than the Ru’at el-Ghanam Middle Neolithic, perhaps indicating that Ru’at el-Baqar stone working was either less important or that the strong sharp edges available without effort on quartz became particularly desirable (Wendorf and Schild 2001b, p.438). At E-75-8 the notches are very crudely shaped, “made by a single blow” and only sometimes provided with additional retouch (Nelson 2001, p.395). Emphasis was also placed on raw materials on which tools were made. This represents more investment and intervention in the output than the manufacturing approach implies.

At the same time, bifacially worked tools appear for the first time, suggesting a dichotomy between a high level of expediency on the dominant part of the assemblage and an intensified and optimized input into a very limited part of the assemblage. Bifacial tool manufacture is not necessarily very time-consuming, but specific knowledge and experience are required from core preparation to flaking technique, and cores and flakes need to be prepared with a view to the final object, requiring a specific reduction strategy based on specific ideas and combinations of task-related activities. These may fit into the category of “objects of thought” defined by Edmonds as partly symbolic as well as portable and functional, requiring a high degree of preparation and anticipation (Edmonds 1995, p.42).

The difficulty of accessing flint, suggested by Close above, was balanced by the use of other materials, showing a versatility and adaptability that are consistent with an opportunistic and optimizing strategy, and the dominance of quartz for the majority of tools shows a shift in the balance of technological strategies. As Wendorf and Schild say, “With little energy investment in the acquisition of this raw material, informal quartz flakes could be produced, used and discarded at minimum cost” (2001c, p.440). In Shea’s terms, the strategic approach combines optimisation (the dominant strategy) with satisficing (a minor element). There are no signs of intensification in the stone tool manufacturing strategy.

Figure 11 – Lithics and worked bone from E-75-8 (Nelson 2001, p.399, figure 11.10).

Figure 11 – Lithics and worked bone from E-75-8 (Nelson 2001, p.399, figure 11.10).

a, perforator; b, endscraper; c, lunate; d, truncation; e, retouched piece;

f, denticulate; g, groundsetone; h,i, worked bone).

Groundstone equipment

Groundstone equipment was found throughout the Ru’at el-Baqar (figures 11-g; figure 12). At E-92-7 grinding implements consisted of 7 fire-cracked fragments of sandstone quarzitic sandstone, sandstone and granite, three of which had two grinding faces. At E-75-8 Ru’at el-Baqar hammerstones were found, together with handstones and lower grinders. They were made of quartzitic sandstone, sandstone, granite and one example each of petrified wood and quartz, and not all of them were complete, some of them very fragmented (Close 2001, p.382; Nelson 2001, p.403). At E-92-4 grinding stones of sandstone and basalt were found, mainly away from hearths. The shapes varied considerably, as did the sizes, but most featured shallow bowls. Some had grinding areas on opposing surfaces and one had two grinding areas on the same surface. At E-77-1 125 handstones were found, of which 476 were fragments. At E-94-3 (figure 12) grinding equipment included 133 whole and 174 fragmented pieces of handstone and 16 complete and 164 fragments of grinders. They were made of quartzitic sandstone and had one or two working surfaces.

Throughout the Ru’at el-Baqar, large notched stones were found (e.g. figure 10-c), but they are particularly prominent at E-94-2, where twenty two were found, made of Nubia sandstone with two or more notches midway along opposing edges. They are found near the hearths and it is proposed that they may have been tethering stones (Mohamed 2001, p.424).

Figure 12 – Site E-94-3, Groundstone artefacts: a, milling stone;

Figure 12 – Site E-94-3, Groundstone artefacts: a, milling stone;

b, handstone; c, notched stone (Source: Mohamed 2001, p.461, figure 13.16)

At E-75-8 two items described as palettes were found. They were unknown in the previous Ru’at el-Ghanam so are novel in the Ru’at el-Baqar. Both are made of coarse-grained sandstone which was pecked into shape, producing thin artefacts, one that was sub-rectangular and one sub-circular. Although there is no direct indication of their function, it is possible that they were forerunners of the palettes that appeared in the later Final Neolithic cemetery at Gebel Ramlah near Gebel Nabta.

In summary, there does not appear to have been a particular design concept for grinders. They come in a variety of shapes and sizes and might have single or opposed working surfaces. This suggests that they were built at a household level and that there was no cultural pressure towards standardization. Grinding stones abandoned at sites for future use suggests that the value of such items was in situ at places where groups came to rest, rather than as part of their movement between nodes. Tethering stones seem to have been fairly standardized but this appears to have been due to functional requirements and experience rather than a design concept. The two palettes are interesting, but apart from noting their presence, there is no generalization possible, particularly as the two take very different forms.

Ceramic container technologies

Whilst the changes to lithic technology were relatively minor, the differences between the Ru’at el-Ghanam and the Ru’at el-Baqar ceramics were considerable. Following a tradition established in the Early Neolithic and retained throughout the Ru’at el-Ghanam, a range of new ceramics was introduced in the Ru’at el-Baqar at sites like E-92-7, E-94-2 (671 sherds representing three types of pottery) and E-75-8, eliminating the thick-walled smoothed-over spaced rocker-stamped bowls, to which the new types show “no points of resemblance” and were “an unrelated ceramic tradition” (Zedeño 2002, p.53). The new types are characterized by fine paste, a relatively small volume of fine temper made of ground sherds minerals, sand and/or organic materials. All appear to have been made on playa silts in the area but the chemical patterning could have been the result of multiple manufacturing locations within the desert (Zedeño 2002, p.53, 57, 59). They were usually in the form of beaker-shaped vessels, as well as some small bowls, with thin walls less than 7mm thick, and show the first evidence of controlled firing (Nelson 2002a, p.7). Decorative schemes show a completely new approach to vessel treatment. Instead of being incised or stamped, entire surfaces were used to emphasize surface colour and subtle texture. Surface treatments included the use of burnishing, smoothing, scraping and slipping, often in combination (Nelson 2002a, p.7). These comprise Black-Topped Ware (figure 13) and Red Wares (figure 14) (sub-divided into 8 variants). The materials, construction techniques, technology, forms and surface treatments are all new, representing a significant departure from previous conceptualizations of pottery. Clays are finer and may have been refined by flotation, may include sand and/or carbonized organic materials and may have required higher firing temperatures, although it is uncertain how these were achieved (Nelson and Khalifa 2010, p.138-9). Decorative schemes largely relied on smoothing, burnishing and slipping rather than decoration applied with tools, creating a very different and more subtle decorative paradigm based on colour. These were whole-surface treatments rather than decorative schemes and patterns. They were all small forms, lacking constricted mouths, making them unsuitable for storage but perhaps making them more useful for milk and blood gathering and eating semi-liquid porridge-like foods (Nelson and Khalifa 2010). Overall the ceramics represent much greater technological complexity than in previous periods. All of the ceramics were hand-made, the majority using the coiling method, but firing techniques were improved, with greater control over higher kiln temperatures producing harder and more durable wares ((Nelson and Khalifa 2010, p.139). It is thought that black-topped pottery was probably achieved by placing a fired pot upside down in hot ash. Different effects on finished items were achieved using different techniques and decorative schemes are technically and perhaps conceptually more sophisticated. Burnishing was achieved by rubbing with a hard object.

Figure 13 – Black-topped pottery

Figure 13 – Black-topped pottery

(Nelson and Khalifa 2001, p.148, figure 4)

Probably produced at the household level on an ad-hoc basis, (Arnold 1985; Balfet 1965; Rice 1987, p.183-91), and perhaps by women (Hodder 1982; Needler 1984, p.184) the knowledge of pottery production may have travelled within and between households over the generations, conforming to a broad set of ideas from both the distant and recent past. The social context within which these changes occurred will be discussed later. Unlike grinding equipment and standard flake-based tools, the ceramics were formed along specific lines, with repeated shapes, treatments and both a common technological approach and a specific preconceived final vision in mind. Both the firing technology and the surface treatment techniques represent not merely a departure from Early and Middle Neolithic technologies but a commitment to a new strategy for ceramic production and a new cultural paradigm. These approaches were already in use in the Nile Valley, suggesting that they represent the adoption of a pristine invention by one or more groups, and the transfer of knowledge to others who seized both the technological opportunity and the cultural ideas associated with it.

Both Eerkens (2008) and Grillo (2014) has made it clear that pottery is completely compatible with a pastoral, mobile lifestyle. Grillo gives the example of the Samburu of north central Kenya who us pottery produced by the Dorobo for a number of purposes but find it particularly crucial during the dry season and during droughts as a means of preserving liquids. Pottery is also important for extracting oils and nutrients from plants, and for breaking down otherwise indigestible plants into forms that could be suitable for human consumption, sometimes by softening and sometimes by reducing toxicity. Use of pottery also postpones spoilage. The Samburu transport pots without difficulty in baskets on donkeys (Grillo 2014, p.117-119). Pottery could be manufactured or acquired in return for other goods if there was anything that groups had that was of value to potential trading partners, including foodstuffs and marriage partners.

Figure 14 – Site E-94-2. Red Ware bowl rims

Figure 14 – Site E-94-2. Red Ware bowl rims

(Source: Nelson 2002, p.36, figure 3.19)

Craft skills

There is no evidence for basketry, matting, rope, textiles, or leather goods, although these must have been present (Hurcombe 2014). As Hurcombe demonstrates, it is difficult to imagine that life would have been possible without them and all the raw materials would have been available in the form of the trees and shrubs that have been noted at Nabta in the Ru’at el-Baqar archaeological remains, particularly the drought-tolerant Acacia, Tamarix and Panicum turgidum species, which today provide fibre for matting, rope and related goods (Mahmoud 2010; Springuel 2006). Tannins from Acacia nilotica could have been used for tanning leather, as it is today (Springuel 2006).

At E-75-8 three pieces of worked bone were found, including one awl and two projectile points, all burned, as well as the fragment of another bone point that was 10mm long and 3mm wide at its widest diameter and was polished all over (Close 2001, p.381). These hint that, as one would expect, a bone tool industry may have been present at Nabta but is simply not represented by the surviving material (figure 11-h and -i).

Ostrich eggshell beads are still found in the Ru’at el Baqar and although they are much less frequent than in the Ru’at el-Ghanam, there are no other differences visible. They were made by perforating an unshaped piece, which was then chipped into roughly circular disks, to a mean diameter of c.6.2mm, before being polished. Out of 131 pieces found only one was decorated, and many were broken during manufacture (Close 2001, p.379-381).

A Red Sea conid shell was found, which had had its apex removed, and is thought to have had a decorative role (Close 2001, p.381).

Mobility

The physical environment is a constraint on the type of mobility that can be practiced in the movement of herds, but in the case of Nabta there are no observable physical constraints on movement between the Nile and the desert areas, a zone that is characterized today by undulating sand sheets. It would have been easier underfoot for both people and animals when it was savannah, but the profile of the landscape would have been very similar, offering few impediments to movement. The ownership of pottery is perfectly consistent with residential mobility and indeed can help to improve pastoralist efficiencies, as in the case of the Samburu of north central Kenya (Grillo 2014, p.106). Larger items, like grinding stones, were left in situ, and hearths were often covered over with protective stones, ready for re-use.

Economic structures

There are very few requirements for structures to support pastoral activities and although Riemer has suggested the use of hunting traps in some parts of the Western Desert (Riemer 2004a) there are no suggestions so far of them being connected with the Ru’at el-Baqar at Nabta.

Cemetery / Religious architecture

There are four types of structure under this category: the stone circle, the tumuli, the so-called complex structures and the megalithic alignments, all constructed from Nubian Formation sandstone that was quarried locally. Although tumuli are known from the Early Neolithic (Bobrowski et al 2006) the complex structures, stone circle and megaliths are new to the Nabta Playa area in the Ru’at el-Baqar. In Complex Structure A the shaped stone above the table rock weighed in the region of three tons (Wendorf and Królik 2001, p.510). I have seen no estimates in terms of number of people or man-hours required to move such a structure, but the investment of time and energy must have been considerable – it required a 3 ton pulley, 12 workers, a wire cable and ropes for the C.P.E. team to pull it out (Wendorf and Królik 2001, p.508).

Food storage systems

The only signs of food storage systems are at E-75-8 where a possible hut was associated with two pits of undetermined function. Given the short-term occupation of the site and the fairly sparse vegetation predicted for the area at this time, it seems likely that there was not sufficient wild plant food to merit storage and that it was collected for immediate consumption. It seem probable that food was eaten on an ad hoc basis, as it was acquired rather than stored.

Transport

It is possible that cattle, sheep or goat were used as pack animals. Close suggests that domesticated livestock were used for carrying heavy stone items during the Neolithic of Safsaf (1996; 2002a), and there is data from ethnographic examples that supports this possibility. The nomadic Fulani, for example, use bulls to carry kitchen utensils and the frameworks for the provisional shelters that were erected along the 5 month migratory route from north to south (Lambrecht 1997, p.29).

Walking was also a perfectly viable means of transporting items that were lightweight and could be strapped to the body, carried or dragged.

Some heavy items, like mortars, were probably left in situ when people knew that they would return to favoured locations.

Fuel

Given the available wild fauna, and assuming that domesticated herds were the main form of dung provision, dung should have been readily available, particularly concentrated beneath trees that would have provided shelter. Linseele (et al) 2010 attest to the large quantities of fuel that can be assembled from herd animals, and there are numerous modern examples of dung being used as fuel (for example, Butler 2002, p.181-2; Evans-Pritchard 1940, p.258; Hassan 1988; Hobbs 1989, p.90, p.104-6).

Burning wood, which was a relatively scarce resource, and one which was not readily renewable, would have been a much higher-risk option for the long term security of the environment, as recognized by Eastern Desert Bedouin today, who enforce strictly encoded social and religious prohibitions established to protect living trees (Belal et al 2009, p.70-71; Bollig 2006, p.336-337; Harir 1996; Hobbs 1989, p.53; Hobbs et al 2014; Krzywinski 1996; Simpson 1992; Wendrich 2007, p.74). However, in Nabta the number of Ru’at el-Baqar hearths containing plenty of wood charcoal suggest that either dead wood was being used in order to protect live trees (as it often is today) that there were mechanisms in place for ensuring that the host tree was left intact, or that wood was not considered to be in danger of being over-exploited. There is not enough data to select between these alternatives, but it seems unlikely that there was sufficient live wood to provide fuel sustainably. All of the woods that were present at Nabta would have been suitable for fuel, particularly Acacia ehrenbergiana which would have been a particularly good candidate for fuel as it has a relatively low moisture content of 29% and burns very slowly, providing heat over long periods (Belal et al 2009, p.70-71; Springuel 2006, p.4). Today Bedouin in the southern Eastern Desert in Egypt use Tamarix most frequently as it is most abundant, selecting branches already browsed by herbivores but would prefer acacia due to its greater efficiency for fuel purposes. Both are used sparingly (Belal et al 2009).

Craft infrastructure

Kilns or equipment associated with pottery manufacture are missing from Nabta. In so far as lithics are concerned, debitage occurs around hearths, so was not isolated from living areas. There are no signs of specialized craft production areas.

Summary