2.1 Modelling dryland livelihoods

Development economics is the branch of economics concerned with supporting indigenous populations, described by Professor Adedayo (2012, p.12) as “a multidimensional phenomenon involving a broad set of economic, social, environmental, institutional and political factors.” Development economists work to improve conditions for marginalized groups to enable them to survive as functioning communities and economies under changing circumstances. Development economics, and the branch of economic anthropology related to it (Ensminger 2002; Hann and Hart 2011; Wilke and Cliggett 2007), have been innovating rapidly in the last few decades, and one of their key tasks now is to understand the livelihood mechanisms of societies which operate, often very successfully, under marginal or adverse conditions at subsistence level or just above so that solutions can be proposed (rather than imposed) to compliment and build on existing skills and traditions (Behnke and Scoones 1993; Carney 1998; Dalal-Clayton et al 2003; Jallow 1990; Hamilton-Peach and Townsley 2007; Leach and Mearns 1996; Masood and Shaffer 1996; Mortimore 1989). One of the tools central to development is encapsulated by the Human Development Index, based on the idea that there are three essential outcomes for human development: long and healthy life; the ability to acquire knowledge with which to participate in community life; to have access to resources to enable a reasonable standard of living and improve people’s inclusion in decision making processes and their personal independence (UNDP 2015). Once the information has been assembled and the organization of a given livelihood understood, the best measures for sustainable development can be assessed (Binns 1992, p.157). Data capture is therefore an important part of the activities of development economics, as it is of archaeologists and anthropologists. The importance of capturing all the variables that act on a society and its ability to adapt or change is what makes many development economics perspectives so useful.

Fine-grained studies into how modern communities are composed, interact with each other and how they make decisions have been important aspects of these approaches (Chambers 2008; Chambers and Conway 1992; Perrier 1995; Sumner and Tribe 2008). For example, within these studies social factors and unpredictable environmental resources have been factored in where they had formerly been disregarded (e.g. Behnke and Scoones 1993; Scoones 1995b; Dasgupta 1997, p.4-5). Approaches have been developed that looked closely at how societies work in practice and what sort of variables must be taken into account in order to improve economic and social sustainability. It became clear that numerous aspects of a livelihood need to be considered in order to assess how decisions are made and what leads to sustainability as all unified economic systems are associated with mechanisms to protect group identity and social organization. This usually incorporates ideas like religion, justice, ideology, leadership, individual identity and long-standing tradition (e.g. Abraham 2006; Eyhorn 2006; Jallow 1990; Manger et al 1996; Masood and Shaffer 2006; Dasgupta 1997; Cliggett 2005; Sen 1999) together with individuals’ perception of risks and their own inclinations (Eyhorn 2006, p.44-45; Sayer and Campbell 2004, p.102), factors that modern development economists now take into account when any change to an economic system is proposed. They also involve the idea of communal identities, based around internal information flows, leadership and the formalization of external relationships (Manger et al 1996; Hobbs 1989; Sen 1999).

The same problems faced by development economists are exponentially more difficult for archaeologists who strive to understand all the variables that may influence societies at points in time and space, especially where new opportunities and constraints come into being. Archaeologists face a different challenge from development economists and anthropologists, because they are working with datasets that cannot be verbally interrogated or empirically observed in all their living detail. This is particularly the case for research into pastoralists whose mobile lifestyles leave somewhat ephemeral remains (e.g. Barnard and Wendrich 2008; Bernbeck 2003; Cribb 1991; Honeychurch and Makarewicz 2016, p.349-50; Leary 2014). In archaeology, where the quantity, quality and type of data is often a limiting factor, one of the main challenges has been to find ways of portraying the various integrated aspects of a livelihood without being excessively biased towards one aspect of the data (e.g. ecological or economic) to the detriment of all other (e.g. social and cultural). This has been most obviously captured in the conflict between processual and post-processual approaches discussed by a number of authors (e.g. Dark 2013; Johnson 2010; Trigger 1996), but is also the result of the way in which archaeological post-excavation work is organized and published (Hurcombe 2014, p.152; Lucas 2001, p.105; Redford 2008, p.23; Weeks 2008). As Trigger explains (1995, p.450) there is “growing support for the position that while important aspects of human behaviour can be understood as rational adaptations to ecological, demographic and technological factors, all cultural change takes place within a context of beliefs and practises that guide human behaviour.” This view has been shared by other archaeologists, anthropologists and economists who attempt to blend both economic and social perspectives (e.g. Barich 1988; Dewey 1966; Harvey 2000; Kent and Vierich 2008; Moss 1992; Sen 1999). As already highlighted above, a similar problem has existed in development economics, where emphasis on certain aspects of livelihoods at the expense of others has led to failed attempts to improve the sustainability of high-risk groups (e.g. Binns 1992; Manger et al 1996; Sen 1999; Masood and Shaffer 2006; Dasgupta 1997; Ellis et al 1993; Cliggett 2005). To address this problem, new qualitative ways of capturing and modelling data about communities living in stressful environments have been applied to development economics and adopted in this thesis.

The challenge for development economists was to devise a way of modelling that would capture sufficient data whilst not oversimplifying the livelihood that it is supposed to represent. The primary potential value of descriptive modelling is that it can be used to break down often complex data into digestible chunks, enabling the overall pattern of competing influences to be analyzed, understood and compared. As Sayer and Campbell put it, “simple indicator sets are desirable, but it would be foolish to expect simplicity when dealing with complex systems” (2004, p.218). The prime explanatory variable that influences an outcome or set of outcomes may be different on a case by case basis, and models will need to include the possibility that a number of variables and a number of outcomes are possible in any situation (Dasgupta 1997), a point also recognized by archaeologists (e.g. Bettinger 1993). The economist Partha Dasgupta, suggests that “[T]he art of good modelling is to generate a lot of understanding from focusing on a very small number of causal factors” (Dasgupta 1997, p.9). He believes that modelling can be used “to make predictions of what the data that haven’t yet been collected from the contemporary world will reveal” (p.10). This suggests that there is the potential for a carefully chosen modelling technique to handle an incomplete data set, a thought that has obvious appeal in archaeology.

Different models are designed for different tasks. Some models set out to represent the complexities of production systems but are not intended to be tools for gathering and anzlyzing data. They may be convoluted and multi-layered, with numerous linkages demonstrating how different elements are connected (see figures 2.1 and 2.2) and are useful for representing complexity within communities. Other models, like the Sustainable Rural Livelihood model, are designed to be flexible tools that incorporate idea that a community may lie anywhere on a continuum of relatively simple to more complex economic and social arrangements.

Figure 2.1 – Components in sheep production (Spedding 1975, figure 2.16, p.32)

Figure 2.1 – Components in sheep production (Spedding 1975, figure 2.16, p.32)

Figure 2.2 – Conceptual box-and-arrow model of integrated resources

Figure 2.2 – Conceptual box-and-arrow model of integrated resources

(Sayer and Campbell 2004, p.115)

In this thesis there is an explicit acceptance that it is valid to examine the activities of modern pastoralists and hunters in order to understand the repertoire of alternatives that would have been available in the past and is discussed in section 2.8. Ethnographic data was used as a starting point to find a modelling technique that was appropriate for assessing archaeological data. Only by understanding the potential patterns of behaviour that may be detectable in the past could a suitable model be identified. At the most basic level, potential communities may be characterized as a series of ongoing choices about economic activities, social organization and quality of life. On a day to day basis, strategy and choice may be influenced by a number of factors all set within an inherited social and cultural context (Cashdan 1990; Jallow 1990; Tainter and Tainter 1996; Carney 1998; Moritz et al 2011; Mortimore 1998; Sen 1999; Sayer and Campbell 2004). The next task was to identify an appropriate model.

A number of relevant models for resolving developing world problems have been created by development economists. One of the earliest and most influential models was that of Arthur Lewis, whose core ideas were that traditional economic models could not be applied to subsistence (agricultural) economies and that there is very little capital endowment in these sectors. He contrasted this with the capital driven urban sector (Lewis 1954). Since then many other models and solutions to economic difficulty in developing countries have been proposed, some of which were considered for this thesis, but were rejected. These include Duncan’s influential POET model (Duncan 1961, 1964); Ilbery’s Point Score Analysis system (Ilbery 1975, 1977); the Integrated National Resource Management (INRM) approach (e.g. Attah-Krah 2006, Campbell et al 2001, Douthwaite et al 2004); the SEIC model (Tabara and Pahl-Wost 2007); the Rural Livelihood System (RLS) model (Baumgartner and Högger 2004); and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment conceptual framwork (MEA Board 2003; MEA 2005). Most of these models emerge from the basic idea that sustainability can only be achieved when a number of important components are fully integrated and fully functional, as expressed in a simple Venn diagram (figure 2.3):

Figure 2.3 – Venn diagram of components necessary for a sustainable livelihood

Figure 2.3 – Venn diagram of components necessary for a sustainable livelihood

(Rosen and Kishawy 2012, p.156 )

Duncan’s influential POET model (Duncan 1961, 1964) was a useful start but was too simple for the purposes of this thesis, being deterministic in its assumption that only these four components play a part in defining a livelihood system: population, environment, technology and organization (figure 2.4). Population includes demographic variables like size, age, and fertility rates. Environment comprises all the natural resources available in an economy. Technology is the means by which environment and population are mediated and ties the user of the technology into tasks relating to manufacturing and raw material acquisition. Organization refers to any organizational structure within society, be it political, economic, religious, cultural or any of another number of formal or informal arrangements. Its importance lay in recognizing that environmental factors were not the only pre-condition for sustainability, that components must be interactive and involve feedback systems, and that these interactions are multi-directional. However, terming it an ecological complex (Duncan 1961) indicates that Duncan still incorporated the idea that ecological factors dominate, with a flow from non-material ecological matters to dependent social and economic structures. It was very influential and is certainly the basis of other future attempts to model livelihoods, but it now seems very reductionist and fails to capture the complexity of interactions between the different elements in society, the economy and the ecological setting and ignores the role played by culture in mediating between aspects of complex systems.

Tabara and Pahl-Wostl (2007) built on Duncan’s model. They identify four key modelling components: structure, energy and resources, information and knowledge, and social-ecological change within a context of sustainability learning: “the co-adaptive systemic capacity of agents to anticipate and deal with the unintended, undesired and irreversible negative effects of development” (2007). The emphasis is on increasing the capacity of individual agents to be increasingly effective in a social-ecological system. They provide the theoretical SEIC model “to help highlight the key components that should be taken into account when assessing the effects on sustainability of processes for social learning in the management of social-ecological systems” (2007). This integrative model is shown in figure 2.5. The authors argue that sustainability occurs when the socio-environmental system (C) is favourably changed within manageable thresholds by creating adaptive changes in government (S), and efficiently managing flows of Information (I) to reduce the pressure on natural resources and the use of energy (E).

Figure 2.5 – The SEIC model (Tabara and Pahl-Wostl 2007, figure 2).

Figure 2.5 – The SEIC model (Tabara and Pahl-Wostl 2007, figure 2).

S = structure and ruling institutions; E = energy and resources;

I = information and knowledge;

C = social-environmental change and

Zi is the size of the sociological ecological system i.

The SEIC approach is an improvement on the POET model but is still unsuitable for archaeological research. One of the problems was that it it is a tool for promoting social learning, emphasizing the role of individual agents in a way that would be unusable with most of the data being used in this thesis; another is that it is less on understanding the current situation and more to do with managing and delivering sustainable change. It is highly self-conscious and interventionist, using social learning as a device to improve sustainability. Finally, the four SEIC components lack the detail and complexity required for a descriptive and explanatory approach.

I also looked at the Point Score Analysis system developed by Ilbery (1975, 1977) as a means of shedding more light on the way in which people made decisions in pastoral regimes and where cultivation is present. Ilbery’s approach incorporates both economic and “socio-personal circumstances” as components of decision making, including a wide number of variables (Ilbery 1977, p.66), placing a heavy emphasis on the agency and preferences of decision makers. In 1984 he created a typology of hop farmers based on 32 variables that are organized by attributes bsed on family occupation and farm and farmer characteristics (e.g. size of farm, and the age and education of the farmer). He found that personal preferences and the perception of others, rather than purely income-orientated factors, played an important role in decision making. However, although I was prepared to adapt it due to its design for use with archaeological data, none of the data available was rich enough to apply Ilbery’s methodology, although it has potential for discussing decision making in historical agriculture where sufficient documentation is available.

The Integrated Natural Resource Management (INRM) model, modified and employed by different writers in different ecological situations (e.g. Attah-Krah 2006, Campbell et al 2001, Douthwaite et al 2004) has potential for understanding natural and agricultural resource management flows. INRM “involves the integrated analysis and management of the components of production, in such a way that one is able to achieve the products required by man for survival, while maintaining environmental balance and sustainability” (Attah-Krah 2006, p.8). Campbell et al (2001) provide a slightly broader definition of INRM as “a conscious process of incorporating the multiple aspects of natural resource use (be they bio-physical, socio-political or economic) into a system of sustainable management to meet the production goals of farmers and other direct users (food security, profitability, risk aversion) as well as the goals of the wider community (poverty alleviation, welfare of future generations, environmental conservation)”. However, although (INRM aims to place people at its core, and solving human problems is its essential task, it is explicitly economic and ecological in its outlook, leaving little room for social drivers, as shown in figure 2.6. It was also developed for agricultural production, reflecting the fact that the term was first coined in 1996 by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) system, a coalition of 15 international research centres (Douthwaite et al 2004, p.323) and is always geared towards that type of economic activity. Although most approaches agree that it is necessary to understand the system under analysis it, and that “modelling is a practical approach to deal with variables that change more slowly than the length of a project” (Douthwaite et al 2004, p.324) there is also no agreed-upon shared model in INRM. Finally, it depends on a very high granularity of economic and ecological data that is often missing from prehistoric contexts.

Figure 2.6 – Components and interactions in INRM

Figure 2.6 – Components and interactions in INRM

(Source: Attah-Krah 2006, figure 1, p.10)

The Rural Livelihood System “mandala” (RLS) has a number of areas of similarity to the Sustainable Rural Livelihood (SRL) model but differs in a number of significant areas (figure 2.7). It is more inductive, emphasising the metaphoric and symbolic, giving much greater emphasis to emotional dimensions and inner realities (Eyhorn 2006; Ludi 2009; Baumgartner and Högger 2004). As well as economic and ecological factors, the RLS puts considerable emphasis on how these dimensions and realities contribute to decision making: “This inner reality can never be fully explored by outsiders, but it ‘shines through’ many perceptible phenomena like a person’s enthusiasm, aristic creativity, sociability or trance” (Högger 2004, p.38). A number of examples are given in Baumgartner and Högger (2004), showing how effective a tool it can be, but for the purposes of this thesis there is no way of accessing many of these areas of emotional and personal decisions in livelihood management.

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) model (MEA 2005; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Board 2001) was also considered. The MEA was initiated in 2001 by the United Nations (UN), with the objective of making scientific assessments of the consequences of ecosystem change and the action needed to ensure conservation and sustainability of those ecosystems, with special reference to their contribution to human well-being and improved decision making (MEA 2005). It operates under the assumption that human activity is undermining the capability of ecosystems to meet human demands for food and clean water: “The human species, while buffered against environmental immediacies by culture and technology, is ultimately fully dependent on the flow of ecosystem services (MEA Board 2003, p.1). It is designed to operate at the regional level and is intentionally focused on scientific as well as cultural intervention to resolve ecosystem problems (see figure 2.8). Although it recognizes four types of productive capital (manufactured, human, social and natural) (MEA Board 2003, p.29) its emphasis is on initiating ecosystem change rather than capturing existing livelihoods. Lenssen-Erz and Linstädter (2010) have used elements from the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) model (MEA 2005) to develop a methodological approach to assessing change in the prehistoric past.

Figure 2.8 – MEA ecosystems conceptual framework

Figure 2.8 – MEA ecosystems conceptual framework

(Source: MEA Board 2003, Box 2, p.9)

The SRL model is far more helpful at a community or group level, capturing data to understand how communities operate within a relatively narrow catchment at any given time. The MEA concentrates on capturing change between conditions. The two would probably work well together, but the SRL model is explicitly asset-driven and includes an assessment of long term sustainability as a requirement for the completion of the model, into which are incorporated potential opportunities and vulnerabilities.

The Sustainable Rural Livelihoods (SRL) model was developed in the early 1990s by a number of writers (Ashley and Carney 1999; Carney 1998, 1999; Chambers and Conway 1992) under the auspices of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Department For International Development (DFID). It was designed to serve as a tool to assist analysts with some of the difficulties experienced by development economists who were trying to understand how to influence decisions of those operating subsistence economies for the purpose of improving their livelihood prospects (Campbell 2001; Chambers and Conway 1992; Dalal-Clayton et al 2003; Dixon et al 2001; Frankenberger et al 2000; Homewood 2005). An early model, based on Carney (1998) was incorporated into DFID Guidelines (DFID 1999, figure 1, p.1), shown below (figure 2.9), demonstrating its intention to characterize different economic systems not in terms of modern measurements of poverty and wealth, but in terms of vulnerability, opportunity, marginality and comparative advantage. Sayer and Campbell used the same elements illustrated in the DFID version but emphasized the dynamic linkages between them (Sayer and Campbell 2001) shown below in figure 2.10. A more recent version added the “Personal” category to the Asset Matrix (Hamilton-Peach and Townsley 2007), shown in figure 2.11, below and described briefly in table 2.1 and in more detail in Chapter 7, section 7.3.8. The Sustainable Rural Livelihood Approach was considered to be the most promising of the various options.

Figure 2.9 – The Sustainable Livelihood model in the DFID Guidelines

Figure 2.9 – The Sustainable Livelihood model in the DFID Guidelines

(DFID 1999, figure 1, p.1)

Figure 2.10 – The dynamic nature of assets in a modern development

Figure 2.10 – The dynamic nature of assets in a modern development

economics scenario (Sayer and Campbell 2001, figure 10, p.218)

Figure 2.11 – The Personal asset added to the Asset Matrix in 2007

Figure 2.11 – The Personal asset added to the Asset Matrix in 2007

(Source: Hamilton-Peach and Townsley 2007)

The SRL model has a number of benefits that render it more suitable than those described above. Although it certainly divides livelihoods into components it is much less reductionist and deterministic than models like Duncan’s POET model (Duncan 1961) and the INRM model (Campbell et al 2001). Even Tabara and Pahl-Wostl’s SEIC model, which built on Duncan’s approach, builds in a deterministic view of how sustainability can be achieved, which minimizes its use for the investigation of a broad range of possible livelihoods and outcomes. The separation of assets and variables in the SRL approach, by contrast, is non-deterministic, allowing any number of variables to act on a broad range of assets. Ilbery’s Point Score Analysis has potential for scenarios where there is high resolution of data that allows the quantification of variables, a feature shared with the INRM model, but for this particular study, where activities cannot be quantified with any confidence, the SRL approach is far more flexible. Closely related to the SRL model is the Rural Livelihood System (RLS), but this was rejected in favour of the SRL approach because the RLS relies very heavily on metaphoric, symbolic, emotional aspects of living and inner realities. These are much easier to approach in anthropological interviews and observations than archaeological research, and therefore not as easy to apply to archaeological contexts, although they dovetail with archaeological interests in phenomenology and agency. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) model is ecologically driven, designed to prevent ecosystem problems. Although it has potential for use at the landscape level in archaeology, it is not easily scaleable.

As the emphasis in this thesis is on livelihood strategies, the evidence-based Sustainable Rural Livelihood model, which incorporates social and cultural components and concepts of personal well-being along with economic and environmental data, is considered to be the most appropriate tool for the type of data and the questions being asked of it in this thesis, balancing deductive and inductive approaches and combining both descriptive and explanatory components. It has been designed to observe trends over time and in space and to look at opportunities, shocks and stresses and the impacts that these may have (DFID 1999; Morse et al 2009). Whilst putting any complex system in a diagram carries the risk of appearing to freeze something dynamic and endlessly shifting, it is still helpful to have a working model with which to capture the relationship between different components of livelihood management, and which explicitly incorporates the idea that change is integral to society.

The SRL model shares with other approaches the benefit of separating assets that can be defined in the archaeological record from variables that may have acted upon them, but it is much less determinative in what these variables are, and assigns equal value to each of the assets upon which they may act. This leaves far greater flexibility for testing hypotheses about social and economic activity and change, providing the potential to gain insights into archaeological questions about the prehistoric past.

Finally, the asset matrix places a requirement upon the researcher to present the available archaeological material in a formal and coherently structured form. This is invaluable for assessing the quantity and quality of the data available, for assessing archeological material in terms of livelihood information, and for using asset summaries from different sites for comparative purposes. Although archaeological reports are organized to reflect excavation strategies and post-excavations specializations, it was hoped that the data required to assess the livelihoods that these excavations represented would be available in the published reports.

2.2 The Sustainable Rural Livelihood Model

2.2.1 The Integrated Model

The SRL approach was first promoted by the United Nations Development Programme in 1990. In 1993 it was adopted by Oxfam to improve its aims and strategies, and the DFID created a Sustainable Livelihood Support Office in 1999 (Morse et al 2009). Small (2007, p.27) describes the SRL approach as a “paradigm shift in international development thinking.” As it is designed as a tool to first record and then assist with the assessment of data, it is proposed that it has a potentially similar value in archaeology. It takes into account that all people demand a minimal set of requirements for survival but that after basic survival is secured, other aspects of life are also essential for well-being. It examines all aspects of lives, divided for analytical purposes into six categories that make up the SRL matrix. Where it becomes more than merely a graphical representation or a static snapshot of a society is in the exploratory and explanatory power of the variables that act, all the time, on the matrix and the ways in which real people manage the relationship between their lives and the variables that act upon those lives. The role of these fundamentally human goals can be a factor in how communities assess internal dynamism and external change or adopt new approaches in their livelihoods. This means that to be truly sustainable, rather than just surviving societies, however simple, should be understood in terms of those social and personal conditions and aspirations as well as purely economic and environmental ones. Today the SRL approach creeps into all sorts of studies, even when not explicitly referenced (see for example Dixon et al 2001. p.15, figure 1.5; FAO 2000).

There are a number of advantages of the Sustainable Rural Livelihood (SRL) approach from an archaeological perspective are as follows. It can model complicated aspects of socioeconomic systems and the linkages between them transparently (see figure 2.8). It incorporates the ideas that whilst sustainability may be essential for survival, other less economically-driven factors which also influence human responses to alternative options are given equal weighting. It builds in the idea of multiple variables potentially operating on assets. It allots equal importance to subsistence and social assets. It encourages users to think about how different aspects of the matrix will result, under certain conditions, in different outcomes (see, for example, the radar diagram in figure 2.15). It can help to assess how successful (i.e. sustainable) a livelihood strategy can be under the given conditions and gives a specific definition of sustainability, against which livelihoods can be measured. It provides an all-inclusive approach to livelihoods. The graphic representation of the model in figure 2.8 makes the approach unambiguous. Although not designed specifically for comparative studies in either space or over time, I suggest that it is entirely suitable for those purpose, demonstrated in Chapter 9. It is compatible with the use of ethnographic data. The model does not underestimate the complexity of small scale production systems, and it is substantive, as exemplifed by the case studies.

The standard manual on the subject of the SRL framework, Pastoralism and Sustainable Livelihoods: An Emerging Agenda (DFID 2000a) explains the SRL model as follows

It views people as operating in a context of vulnerability. Within this context, they have access to certain assets or poverty reducing factors. These gain their meaning and value through the prevailing social, institutional and organizational environment. This environment also influences their livelihood strategies – ways of combining and using assets – that are open to people in pursuit of beneficial livelihood outcomes that meet their own livelihood objectives (DFID 2000a p.14).

Carney 1998, who was instrumental in the development of the SRL model, helpfully defines a livelihood, making it clear that it is not merely task-orientated (p.4):

A livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets (including both material and social resources) of activities required for a means of living.

Looking specifically at the idea of sustainability, the concept is derived from the knowledge that communities need to respond to short and long term vulnerability. As a working concept, sustainability has much in common with Resilience Theory, which has been discussed by various disciplines, notably psychology, and has also been adopted by some branches of development economics (Gichuhi 2015). Both look at ways of ensuring the SRL model incorporates the idea that sustainability may be influenced by other factors embedded in social frameworks and ideas of desirability and choice, which are equally important to human well-being and social security. Chambers and Conway (1992, p.7) elaborate as follows:

A livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets . . . and activities required for a means of living; a livelihood is sustainable which can cope with and recover from stress and shocks; maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets and provide sustainable livelihood opportunities for the next generation; and which contribute net benefits to other livelihoods and the local and global level in the sort and long-terms.

An important point is that the SRL model is orientated towards people and how they live their lives rather than just the resources they use or the governments that manage the economies within which they exist (Carney 2003, p.13; Farrington 1999, p.4; DFID 2000a, p.3). Whilst it may seem that the SRL approach is driven by assets rather than people, at its heart is the desire and the practical need to find out what motivates people, what their priorities may be and how to help them restructure whilst retaining the ideologies and social institutions that they value (Carney 1998), incorporating ideas of both economic and social risk (FAO 2001b; Moritz et al 2011). The relationship between the Asset Matrix and the livelihood variables expresses some of this complexity.

The SRL model (figure 2.12) conceptualizes assets in the form of the Livelihood Asset Matrix, six criteria or livelihood characteristics, which sit within a context of vulnerability and opportunity. The Asset Matrix hexagon is the data capture vessel. At the centre of the hexagon, the point represents zero access to assets, and the radiating lines indicate differing to maximum access to assets. There is particular emphasis on the importance of variables that may influence the various components of a livelihood, captured in the Livelihood Variables tables, and how these may transform livelihoods. These variables are often outside the control of the people who are most effected by them. Although they are often negative, including drought, disease, climate change, the collapse of social networks and other shocks and longer term trends, they may be positive too, including opportunities offered by new products, services and technologies. The Livelihood Status matrix is framed within the context of flexibility. Flexibility represents the ability and willingness to make short-term strategic choices and take up economic, cultural and environmental opportunities when available, and to employ cultural devices to sustain a sense of community and individual identity, and to use these techniques to incorporate and modulate change.

Figure 2.12 – The SRL Model, modified for use in archaeology

Figure 2.12 – The SRL Model, modified for use in archaeology

2.2.3 The Components of the Livelihood Asset Matrix

The starting point for collecting and categorizing data is the Livelihood Asset Matrix, which represents the livelihood status of a group or community. The Livelihood Asset matrix provides a series of headings which make up the main assets and inputs which go into making up a community. The DFID Sustainable Livelihood Guidance Sheet emphasises that the benefit of the matrix is that it brings to life important inter-relationships between the various assets (DFID n.d.), reflecting the mix of assets available to people and how these influence their livelihood strategies.

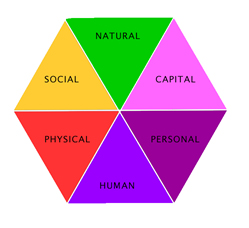

The model analyses the influences of a number of variables on a core matrix of assets, which are as follows (figure 2.13):

Figure 2.13 – The livelihood asset matrix

Figure 2.13 – The livelihood asset matrix

The above livelihood asset matrix can be expanded to show how these components are described and what the research demands may be, shown in figure 2.14 below. These are discussed further below, and. In Chapter 7 it is suggested how archaeological measures might be applied for each component and these are captured in Appendix G.

Figure 2.14 – Variables in the asset matrix, based on the DFID Guidelines (DFID 1999)

Figure 2.14 – Variables in the asset matrix, based on the DFID Guidelines (DFID 1999)

The assets can be summarized as follows. These are developed in Table 2.1, where the criteria for recognizing the asset components archaeologically and characterizing them are also shown.

- Natural (environmental and biological resources, maintenance of biodiversity)

- Subsistence (ability to acquire/produce food, store, save and trade)

- Human (ability to support physical well-being and provision of good health)

- Social (resources for mutual support, group identity, maintenance of traditions and group spiritual fulfilment)

- Personal (ability to achieve individual satisfaction within a community)

- Physical (Infrastructure required for pursuit of livelihood choices, including technology, shelter, transport)

It should be noted that some components may appear in more than one asset class. For example, livestock is not only a subsistence asset but is also a human asset and may also be a financial and social asset (DFID 2000a, p.7, 16-17; Evans-Pritchard 1940). Similarly, when resources are limited, assets may be under-represented in one area if they have been invested significantly in another. An obvious example is the depletion of natural assets after over-grazing or over-hunting. Archaeological indicators of the components in the asset matrix are shown in more detail in Chapter 7.

The assets are broken down into a series of components shown in Table 2.1, below, which are described in detail in Chapter 7. This consists of three columns: Assets, Characterization and Sustainability. Assets are the sections of the hexagon. Characterization refers to how these are perceived and evaluated. Sustainability is the determination of whether what is observed can be sustained in the longer term. Sustainability may be economic or social, and is usually both as they reinforce each other. The SRL matrix frames livelihoods within functional and pragmatic categories that avoids the vague and often disputed concatenations like “socio-economy” and “socio-culture” and does not allow for often dichotomous simplifications of livelihoods. The data in table 2.1, below, is based on Carney 1998, Corloni and Crowley 2005 module 5, the DFID Guidelines 1999, Morse et al 2009.

Table 2.1 Characterization of assets and measures of sustainability

Table 2.1 Characterization of assets and measures of sustainability

Access to assets may change constantly. Figure 2.15 demonstrates the dynamic and interactive nature of assets and their relationship to one another in one example. In the original diagram all assets are shown having maximum potential but the strength of assets is always relative to other assets. The relationship between assets can be expressed using the asset matrix, by altering the hexagram (or in earlier versions the pentagram).

Figure 2.15 – DFID pentagon for a specific urban context.

Figure 2.15 – DFID pentagon for a specific urban context.

In this example the livelihood seems unsustainable as it shows poor

human, financial (subsistence) and natural assets together

with declining access to physical and social assets (DFID 1999, section 2.1)

Figure 2.16 – Radar diagram from Chatper 9 and Appendix H showing

Figure 2.16 – Radar diagram from Chatper 9 and Appendix H showing

the radar diagram from the Hadendowa test case study,

demonstrating that whilst relatively sustainable in some areas, the

cutting of trees for fuel and charcoal for urban centres has

undermined natural resources, and that social structures are being

impacted by the loss of young men and families to the same urban areas

Radar diagrams can be used to show how assets are stronger in some parts than others. Obviously, a major question is how to assess each component, to define measurables. Whatever weighting systems are adopted by the practitioner, the numbers are derived qualitatively, not quantitatively. The numbers are being used to deliver a graphical representation of a subjective system of values. My approach, based on Nelson et al (2016) is discussed in detail below in section 2.4.

2.2.4 The Livelihood Variables

After the livelihood asset matrix has been completed, the model goes on to show how these different assets can be modified by vulnerabilities and opportunities, which cause different livelihood strategies to be followed and different actions to be taken. Vulnerability “refers to contingencies and stress, and difficulty in coping with them” (Manoli et al 2014). Community assets are therefore seen in the wider context of external impacts, the decisions that need to be taken in the face of those impacts, and the resulting livelihood outcomes that result from these complex variables. These are listed in figure 2.17 under the following headings: Vulnerability Context, Opportunity and External Processes. Variables are not always easy to assess. As archaeologist Robert Bettinger emphasises, “it requires hard choices about the variability that is important and the variability that is not” (Bettinger 1993, p.44).

Figure 2.17 – Livelihood variables within the SRL model

Figure 2.17 – Livelihood variables within the SRL model

The situation of risk or security within which groups exist and within which inputs are made and outputs emerge is described as a set of livelihood variables. This includes opportunities and vulnerabilities, and the structures and processes that act upon the way in which livelihoods are managed. Of these, the variable most usually concentrated upon is vulnerability, the shocks and stresses that are faced by any given livelihood (Morse et al 2009, p.5).

The work of both development economists and anthropologists makes it very clear that particularly in areas of environmental unpredictability the concepts of vulnerability and opportunity are central to livelihood maintenance and that the process of managing livelihood systems in these contexts is particularly challenging (Behnke et al 1993; Carney 1998; Mortimore 1998; Sayer and Campbell 2004; Sumner and Tribe 2008). Development economists have spent a considerable amount of time defining what constitute the main vulnerabilities and the opportunities which may become available with those contexts of strategic planning (Behnke et al 1993; Carney 1998; Sayer and Campbell 2004; Sumner and Tribe 2008). The development and anthropological literature provides numerous examples of groups who live successfully in Sahelian and other disequilibrial environments. Examples of such groups who have lived successfully in desert environments are the Beja of Sudan (Manger et al 1996), the Ma’aza of Egypt (Hobbs 1989), the Sandawe of Tanzania (Newman 1970), the Herero of western Botswana (Vivelo 1977), the Barabaig of East Africa (Kilma 1970); the Himba of Namibia (Abati 1998; Bollig 2006), the Woɗaaɓe of southeastern Niger and the Puebloans of southwest North America (Vlasich 2005).

1.2.4.1 Vulnerability Context

The vulnerability context describes the variables that challenge a community’s ability to maintain food production and social structures. The previous section described the assets which make up a livelihood system. These livelihood assets are acted upon by a number of variables which can be understood as vulnerabilities and opportunities. As the primary concern of all groups is basic survival and the minimisation of anticipatory risk (Lavigne-Delville 1997, p.149) understanding vulnerability contexts is fundamental to understanding how groups operate under varying conditions of uncertainty. Stiglitz has suggested that in the past economists have failed to understand the degree to which people are risk averse, and the impact that this has on their response to adverse events, the shocks that can destabilize economies and social structures, and sometimes threaten life (Stiglitz 2014, p.14).

Vulnerabilities and opportunities are dependent upon different environments and on the implementation of novel ideas about livelihood management. They help to determine the available options for a community. Changes to the variables that enable food production which may lead to the implementation of short or long term measures include resource shock (drought, flash flood/storm, disease, altered seasonality), cultural causes (political dispute, human movement, population growth, war, over-use of biomass, spiritual/religious crisis, loss of skills/knowledge), industrial failure (loss of raw materials, loss of skills/knowledge) (Boserup 1965, 1981; Dei 1990; DFID 1999, 2000a; Farrington 1994; Fodchuck 1990; Holland 1990; Morse et al 2009; Moritz et al 2011; Robinson 2004).

Within the vulnerability context people have access to certain assets or risk-minimizing techniques, which they can combine to achieve beneficial outcomes even under difficult livelihood circumstances. As Alger (2000, p.347) points out “The concept of vulnerability offers us an analytical framework for unravelling the stereotypes and generalizations that so often blur our vision of real life.” Whilst it is possible to suggest specific types of vulnerability as actors on a given situation, these do not take place either in isolation from one another or from the social context upon which they are acting, including social structure, kinship networks, political entitlements, economic activities and the ways in which ecological constraints are handled.

Vulnerability may also be seen in terms of the erosion of human capabilities and choices which may victimize all members of society but may single out certain community members, like the impoverished, the old, the disabled, children and women (UNDP 2014, p.1), an aspect of life captured in the Personal asset category. The UNDP emphasises that human capabilities are built up and maintained over a lifetime and are the result of life histories and by the interplay of the community with environment and society as a whole. However, even with a lifetime of experiences built on previous histories, short term shocks may have effects that are more than transitory on the future lives of individuals (UNDP 2014, p.3). If vulnerability is defined as “an exposure to a marked decrease in a standard of living” (Stiglitz 2014, p.14) then, again, short term shocks may be exacerbated at the level of an individual who has a less than advantageous position in a community. Nelson et al (2016) identify eight variables as enabling/constraining factors, and by weighting them for each of their case studies, are able to generate a “vulnerability load,” a useful concept that is used in my own case studies and discussed below in 2.4.

Vulnerability, risk and uncertainty are discussed in depth in Chapter 5.

1.2.4.2 Opportunities

Opportunities are ideas, technological innovations or imports, new production possibilities (including new animal and plant types, favourable climatic change, production surplus or any other innovation, adaptation or adoption) that may be leveraged by an individual, household or group in order to improve livelihoods. As Ingold says (1981, p.126) every innovation “whether of local origin or introduced from outside, represents just one of a potentially infinite range of possible solutions to a given problem.” Some of the solutions to vulnerability will depend on new opportunities but opportunity may also represent improvements and refinements to an already successful lifestyle. I have discussed more about opportunity and innovation in Chapter 5. Appendix D describes the resistance of Puebloan Indians of southwest North America when confronted with the potential of both newly introduced and ongoing opportunities. Opportunity has been explored further in each of the case studies.

1.2.4.3 Livelihood Structures and Processes

Livelihood structures and processes include a variety of institutions at local and regional level. These are the social and political structures. In development economics this includes state and governmental influences and the impact of international politics, conflicts and markets (Carney 1998; DFID 1999). These are not applicable to prehistoric contexts, although they would be more appropriate for historical cultures that demonstrated a greater level of complexity. In prehistoric contexts, structures and processes that might impact livelihood variability could include social, contractual and kinship networks, local markets and trade arrangements, territoriality including agreements about land tenure and common-land, local political, leadership or organizational difficulties, and religious or spiritual institutions.

2.2.5 Livelihood Outcomes

The outcomes of the SRL model describe what happens when livelihood variables act on an existing livelihood status (figure 2.18).

Figure 2.18 – The livelihood Outcomes section of the diagram

Figure 2.18 – The livelihood Outcomes section of the diagram

This part of the model looks at the influences external to those dealt with by existing risk management strategies. These may lead to observable change in livelihood situations. Positive outcomes, for example, would be increased production and food security, sustainable natural resource management strategies, lower vulnerability, improved health and life expectation, and overall improved well-being. Negative outcomes are often environmental. Research into modern groups indicates that small-scale societies are not merely passive environmental participants but may set about modifying their environments to suit their needs, sometimes resulting in over-exploitation of the environment, particularly around sources of water in arid locations (e.g. Adriansen 1999, 2008; Binns 1992; Hunn 1993; Rodríguez-Estrella 2012). The degree to which societies are able to respond to changing conditions will depend partly upon the composition of the subsistence economy adopted by a group, the internal social organization, the links with kin and other groups, and the way in which the environment is stable or the degree to which it changes.

2.3 Supporting Models

In some instances it has been possible to work backwards from archaeological data to suggest how certain outcomes may have been influenced. A number of tools to accomplish this are described below.

A graphic tool derived from the SMART (Simple Multi-Attribute Rating Technique) approach is used in “Case Study 2: The Badarian” to represent some of the variables that are involved in managing livelihoods in dryland environments (Goodwin and Wright 2004). The SMART technique is very useful for highlighting important aspects of problems and the various aspects that will need to be taken into account for resolving them, and its main objective is to create a better understanding of the problem (Goodwin and Wright 2004, p.33-34). The full implementation of the SMART approach is a series of steps to assist with decision making, but its main focus is on the identification of attributes that are relevant to a problem for which decisions need to be made. An important process in this multi-stage process is to develop a value-tree, which breaks the problem down into a main overall objective and multiple sub-objectives, to which attributes are assigned and the possible alternative outcomes linked. This part of the technique is used by itself to highlight the relationships between different variables, as in the example below (figure 2.19), which looks at the variables involved in deciding on a crop to plant, discussed in Case Study 2, the Badarian, and in Chapter 9, Comparative Findings.

Figure 2.19 – Components in a decision to grow a particular crop

Figure 2.19 – Components in a decision to grow a particular crop

Some specific questions are further approached using a Quality Function Deployment model (Slack et al 2000) in Chapter 9. It is a more complex version of the “utility function” concept that relates goods to a perceived value of these goods, a perception which can change when conditions change (Kohler and Van West 1996; Rima 1972). Quality Function Deployment (QFD) was developed at Mitsubishi’s Kobe shipyard in Japan and has been used extensively by manufacturers of industrial machinery and developers of interactive products (Slack et al 2000). In industry it attempts to capture what the customer needs and how it might be achieved. It is a very useful way of graphically representing and calculating the importance of different benefits and risks with any given combination of functional choices, allowing subjective scores to be applied to different aspects of human requirements, and showing how they can be achieved. I have used this frequently in the past to translate stakeholder requirements into specific software specifications, but I have adapted it here (figure 2.19) to assess how key human requirements could be met in a given context, how they were actually met, and the absolute importance of each environmental component is, or could be, valued relative to the others. This is particularly useful when a specific component is puzzling. It should be remembered that outcomes will vary depending on the questions asked, and perceived value is a subjective approach and may be evaluated differently by other researchers, so it is useful for working through ideas rather than presenting a definitive answer.

Figure 2.20 – Relative values of cattle, sheep, pig and goat in

Figure 2.20 – Relative values of cattle, sheep, pig and goat in

dryland subsistence economies

In the above diagram (figure 2.20) a simple rating system of subjective values derived from ethnographic data is used to allocate key attributes of each animal, and to see how each animal rates overall. This is discussed in Chapter 9.

In all of the case studies, a system developed by Nelson et al (2016) is used to gauge vulnerability in access to food and to give a top-level assessment of the food resource situation in all of the case studies. Nelson et al describe vulnerability load and list eight variables that contribute to it. Vulnerability load is the “the extent to which each variable contributed to the likelihood that people might experience impacts from climate challenges” (Nelson et al 2016, p.300). The variables are divided into population-resource conditions and social conditions, highlighting that both natural and human variables impact livelihood conditions and the choices that can be made. The variables are ranked using a simple qualitative scale to measure its contribution to overall vulnerability. The variables contributing to vulnerability load are shown in the following table (table 2.2) (Nelson et al 2016, p.300):

Table 2.2 – Vulnerability variables (Nelson et al 2016)

Table 2.2 – Vulnerability variables (Nelson et al 2016)

The qualitative ranking scheme is as follows for measuring each variable, based on contribution to vulnerability (2016, p.300):

- No contribution

- Minor contribution

- More substantial contribution

- Substantial contribution

A score of 1 for variable 1 (availability of food) would indicate that food supply did not contribute to vulnerability and would not therefore be a problem for the community. A score of 4, however, would indicate high vulnerability. A total of all variables (a possible maximum of 32) gives an estimate of how vulnerable the entire community was. By dividing vulnerability into resource and social conditions, the importance of natural versus human influences can be made explicit. In table 2.3 the outcome is divided into two rows: “Data,” which reflects what the actual data indicates, and “Extrapolated,” which uses the combined knowledge derived from the case study and ethnographic studies to suggest more realistic scores. Question marks represent insufficient data. The variables for each case study, using best judgement on the data captured in the assets in the following format (table 2.3):

Table 2.3 – Population-resource and social-resource conditions

Table 2.3 – Population-resource and social-resource conditions

Finally, the risk management strategies discussed in Chapter 5 are compiled into a table and measured qualitatively for both insight into individual risk management strategies and for comparative purposes (table 2.3). I have used a simple yes/no/? rating on whether there is evidence for a practice, but I have also indicated how much confidence there is in the data and the judgement, using a simple High (H), Medium (M) and Low (L) scale. The example below (table 2.4) is copied from the Gilf Kebir case study.able 2.4 – The Evidence for risk management strategies in the Gilf Kebir

Table 2.4 – The Evidence for risk management strategies in the Gilf Kebir

Table 2.4 – The Evidence for risk management strategies in the Gilf Kebir

Where quality of data is low to medium but the corresponding confidence is medium to high, this is because ethnographic data suggests that even though it may not be prominent archaeologically, it is a livelihood management activity that was very likely to have been practiced. The data may be equivocal, but the experience of modern groups suggests that there is a high probability that certain activities would have taken place in conjunction with others shown in the table.

2.4 Initial Testing of the SRL Framework

A major workstream was to explore the full extent to which the SRL model could capture relevant data. This took two forms. First, the framework was used to gather as much pertinent ethnographic data about dryland livelihoods under each of the Asset Matrix and Vulnerability Context sections as possible, in order to develop an understanding of dryland livelihoods and to see how this knowledge could be represented within the framework. Secondly, a specific case study was worked through at a basic level, using data published about the Hadendowa nomadic pastoralists of the northeast Eastern Desert in northeast Sudan, a summary of which is contained in Appendix H. These proved to my satisfaction that the SRL approach was viable and, most importantly, a powerful and useful tool. Much of the data in the first test study was incorporated into chapter 5 as well as in the case four studies. My initial test of the model against archaeological data in a test case study for the Gilf Kebir in both the Gilf B and C phases argued that it had potential where data is sparse.

2.5 Conclusions

It is proposed that the Sustainable Rural Livelihood approach is an appropriate qualitative device for describing, discussing and assisting in the explanation of archaeological data. It was designed by development economists during a re-evaluation of their attempts to understand and improve the sustainability of livelihoods in developing countries by providing balanced insights into sustainable livelihood management. As its focus is the extraction and presentation of data and the exploration of variables that have explanatory value, it is proposed that it has considerable potential for archaeological investigation.

Use of the model for prehistoric contexts implies that a way of compartmentalizing components of societies today is equally appropriate to societies in the past. The model as it stood was certainly not appropriate to prehistoric situations, making reference, for example, to NGOs and global markets. It has therefore been modified to reflect a different, reduced set of variables. As a working tool it has proved itself to be useful and successful in development economics, and although it is an artifice, like all models of human behaviour, it is also a tool for representing reality. The SRL model is not designed to stifle the people it describes; it is designed to provide the tools with which to identify and understand multiple aspects of their livelihoods. The decision to use it for assessing archaeological data was based on its emphasis on data collection, its equal weighting of all components that make up a livelihood and its explanatory aspects.

The next task was to ensure the SRL model that satisfies theoretical approaches to archaeology. Chapter 3 therefore focuses on how the SRL model relates to existing theoretical approaches in archaeology, and how it differs from them.